We’re about 3 weeks into our annual fundraiser. Our goal is $12,500 (same as last year). So far we’ve raised $8,180 from 72 people out of a readership of about 10,000.

If you read this blog, you’re usually ahead of everyone else. You know, years in advance, much of what’s going to happen. The intelligence from this blog is better than what people pay $10,000/year for. Without donations and subscriptions, this blog isn’t viable. If you want to keep it, and you can afford to, please give. If you’re considering a large donation, consider making it matching. (ianatfdl-at-gmail-dot-com).

As I write this I’m eating a sub I bought from across the street. While it was being prepared I chatted with the young woman making it, and she told me about moving from the Canadian Maritimes to Toronto, to, in essence, get a job that pays a little more than minimum wage. Because out in the Maritimes she had trouble getting even that.

As I write this I’m eating a sub I bought from across the street. While it was being prepared I chatted with the young woman making it, and she told me about moving from the Canadian Maritimes to Toronto, to, in essence, get a job that pays a little more than minimum wage. Because out in the Maritimes she had trouble getting even that.

I thought to myself that her experience is one that politicians need to have. Many politicians, of course, have never ever had a bad job. They went straight to a good university and from there to a good job or internship. They probably worked hard for it, and think they deserve what they have, never really seeing all the people whose feet were never on that road, who never had the same shot they did.

Then there are a fair number of pols, though less and less every year, who will tell you about the lousy jobs they had as teenagers, or maybe in their early twenties. But in most cases something is different between them and many working class and even middle class folks.

They knew they weren’t staying there.

When I was poor and working in lousy jobs I used to look in the mirror and see myself at 50, or 60. I expected to still be working at grindingly hard jobs, being treated badly by bosses (because there is no rule more iron than that the worse you are paid the worse your employer will treat you), and still being paid little more than minimum wage. That was the future I saw for myself.

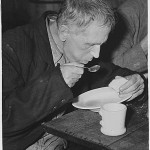

And when I was on welfare, after having failed to find a job for 6 months, and even being turned down by McDonalds (in the middle of the early nineties recession) I wondered if I’d even ever have a shitty job again. I ate cheap starchy food, turned pasty and put on weight. My clothes ran down. When my glasses broke beyond the point where tape would keep them together I literally had to beg the optometrist to make me his cheapest pair and I’d pay him later. (I eventually did.) My life was a daily grind of humiliation.

And that’s what I expected my life to be.

When politicians participate in one of those “live on Welfare for a week/month” programs I’m happy, but I’m also dubious. The difference is that they know they’re getting out in a week or a month. They know it’s going to end. Much as I applaud someone like Barbara Ehrenreich, who lived for months working at lousy jobs, again, she knew it was going to end. She knew that, if push come to shove and she became seriously sick, she could opt out. She knew that if she really couldn’t eat for days, that was her choice.

Living without that safety net, knowing that if something goes wrong, that’s just too bad, changes you. Living without any real hope of the future, knowing that the shitty job you’ve got now is probably about as good a job you’re ever going to have, changes you.

And it changes your sense of what hard work is, of what it means to be deserving. I remember working on a downtown construction site as temp labor, and I’d watch all the soft office workers with their un-calloused hands come out for lunch, and I’d wonder why they got paid two or three times what I did for work that was so much easier (and which, of course, I could do, even if I didn’t have a BA.) At the end of the day they might be stressed, but I’d go home physically exhausted from hard labor and so would my co-workers.

Of course, I got out of that. I’d say “I went back to university”, but even though that’s true, it’s not what got me out, since I never finished my BA. Instead what got me out is that I finally got a couple chances to prove what I could do—I got a temp job in an office, and was one of their most productive workers (they measured it.) Later I got invited to blog, and hey, I can write, even if I don’t have a BA. I got lucky. Like most people who get lucky in work, that luck involved a lot of hard labor, but it also involved luck.

But a lot of folks never get lucky despite the fact that they work hard. Perhaps they aren’t really all that bright (half the population, after all, is below average intelligence.) Perhaps they’ve got some personality issues or weak social skills. Perhaps there’s something not quite right in their brain chemistry. Or perhaps they just never catch a break because they aren’t lucky and their parents weren’t well enough positioned to help them get those breaks.

But still, most of them work hard and earn their money, whether it’s barely more than minimum wage or they did get a bit of luck and got one of the few remaining good blue collar jobs.

But when they look in the mirror, they know that the guy or gal looking in the mirror ten or twenty years from now is probably going to be doing the same thing. And they know that they’re one bad break away from losing even the little they have—one illness, one plant closure, one argument with their boss.

They don’t have a lot of hope for the future, except that it won’t get worse. The life they live now is the best it’s probably gonna get.

Living like that changes you. It makes you see people differently. You understand that there are a lot of bad jobs out there, and that someone’s going to be stuck with them. You know that most of those jobs are either hard or humiliating, and often both. You know that for too many people, a shitty job where they’re abused by their boss is as good as it gets.

This all comes to mind because of how Congress and other politicians have acted throughout the auto bridge loan debate. Folks who passed a bill giving their sort of people: wealthy people who went to good colleges, who work with their minds and not their hands in the financial industry, 700 billion dollars without any real oversight wanted to force a cram down of wages and benefits on auto workers. Journalists on TV who were sympathetic to the bailout, dripped with palpable contempt for the idea of “subsidizing unprofitable companies”, something that didn’t bother them when it was soft-handed professionals like themselves on the dole.

The narrative of the GI generation was “first person in my family to go to college”. They came up from poverty, they probably expected to live in poverty all their life, but when the world changed so changed their chances.

It was a generation of opportunity, but what has happened since them is the “closing of the American elite”. Every generation the odds of someone born poor making it into the elite decrease. At this point about 80% of the working class don’t get degrees. The US now has the least inter-generational social mobility in the Western world (it used to have the most). The elites have become self-perpetuating, and they never had to stare in a mirror and know that they may never have more than minimum wage job; that probably this is as good as it gets.

As a result they have no real empathy or understanding of the vast majority of the middle and working class. The elites know they worked hard to be where they are, what they don’t see is that their feet were put on the path from birth, and that every opportunity was given to them. Opportunities that were not so open to those below them, who have to virtually bankrupt themselves to go to university and whose schools were completely broken, even as the value of BA declines to multi-generational lows. Put yourself in debt for 20 years, and it may still not buy you the good life.

That existence, hand to mouth, with no hope, is something America’s elites have never experienced and don’t understand. For them there’s always another opportunity, always another chance: always hope. And what matters to them is when the “deserving”, which is to say, their own class, is in trouble. So they’ll bail out the financial sector, even though it hasn’t made any more profit than the Big 3 in the past 8 years, and unlike the financial sector, didn’t bring down the world economy, but they won’t help out the undeserving whom they don’t understand.

America has become the most class ridden society in the Western world, far worse than Britain. Congressional seats are passed on to family members and friends like corrupt boroughs in 18th century England. The rich are bailed out and ordinary people left to sink. Responsibility is enforced on the least in society while the privileged are allowed to skate. Sell a gram of pot, go to jail; but kill hundreds of thousands in an illegal war and it’s no big deal.

The elites don’t live in the same world as ordinary people. They have become completely disconnected from that world. This is entirely logical on their part, because for 30 years they’ve gotten rich, rich, rich at the same time as ordinary people haven’t had a single raise. When you’re sitting on the top it’s very clear that all boats don’t need to be lifted and that Americans aren’t all in it together. The elites have done just fine, for over 30 years, while the rest of society went to hell.

So there’s no empathy born of shared experience, of the knowledge that sometimes life sucks and no matter what you do, it’s going to suck, and that that’s the way many people live. And there’s no acknowledgment of a need to make America work for everyone, because for the elites, that’s simply not true: America doesn’t need to work for everyone for things to be good for them.

This then, is how they’ve acted. Plenty of help for themselves, for the people they see as part of their group. And very little help for everyone else. Because the elites aren’t like ordinary people, they don’t believe they have many shared interests with you, and they no longer have any real shared experience.

Expect to eat a lot of cake over the next few years if this attitude doesn’t change. The elites, of course, are wrong. At the end of the day a nation without a solid working and middle class always falls into steep decline.

But, as Adam Smith once said, “there’s a lot of ruin in a nation.”

Nonetheless, as many nations have discovered, that amount isn’t infinite.

This is a republished article from 2009. I think it’s worth putting some of these up occasionally, because most readers won’t have seen the original.

someofparts

I see that in certain family members. At first I didn’t want to believe it. How can they have grown up on the same street I did and turn out like this? Of course by now I do believe it and the result is predictable. As the saying goes, if they (or their spawn) were on fire I would not cross the street to relieve myself on them. A pox on them all. There are good reasons why so many of us want to canonize Luigi Mangione.

NR

Any info you can link on that, Ian? I’d love to find out more about this.

Ian Welsh

The article is from 2009, so, yeah, don’t remember. I’m sure it was true then, I was right on top of that sort of thing at the time.

ibaien

my good friend escaped really ugly rural new hampshire catholic poverty (first of ten kids, thrown out and homeless at 18) and by sheer force of will put himself through nursing school. he’s making tremendous money now but has the deep-seated contempt for the rest of the marginal poor (“why don’t those losers do what i did?”) that i think comes with being a bootstrapper.

all that is by way of saying that we need more politicians who not only lived the experience of generational poverty but also didn’t crab bucket out. good luck finding those needles in the haystack.

bruce wilder

I think I saw this piece the first time around. I certainly thought along similar lines back then, though my lived experience was a step or three (or maybe just ten or fifteen years earlier in the toboggan run of New Deal degeneration) removed, since I did attend ruling class schools, acquiring a couple of diplomas.

My personality or neurotic psychology imposed some limitations in forming personal attachments and pursuing ambitions, but those are stories for a different place and time.

“Most men live lives of quiet desperation” was an observation made quite some time ago. It can be both accurate and projection. Social mobility is a two-way street; traffic in one direction predominates only when a society is growing in prosperity and becoming safer and less brutal, or vice-versa.

One thing that has come more into my political consciousness in recent years is how many of my contemporaries (fellow boomers) are wrapped in a bubble of hypernormalization. That Adam Curtis popularized concept seems to explain so much about the course of centrist politics since 1980, or at least the embrace of unreality and the memory hole. It is really fantastic how much of politics has come to revolve around narrative propaganda with no grounding. Narrative propaganda is nothing new; I myself enjoy some 40-proof aged Whig history from time to time. It is the no-grounding part that continually surprises me (and seems to require liberal use of the memory hole).

This is a long-winded way of saying that I think the apparent lack of concern or empathy among the politically-aware, so-called educated middle classes about the fate of the working classes and the whole of society is a product of evolving circumstances and well-managed propaganda. Most people, I am convinced, simply do not pay attention, reacting like animals in a Gary Larson cartoon to snippets of overheard noise. And, there’s lots of manufactured noise for everyone’s taste.

People certainly notice the homeless. That is an extreme symptom of social and economic decay that is not being hidden. I do notice. I feel politically helpless — there are almost no institutional levers I can see that I could trust to act effectively. I can reject the most callous reactions of others, those who want to criminalize homelessness, but if I am honest, those “other people” are probably just feeling a similar political helplessness and processing it differently, grasping for a solution.

Americans notice their health insurance premiums I imagine. More than rent I am told. (Like most boomers, I have escaped to Medicare.) What can they do politically, but despair? I cannot see any political capacity to deal with it in the U.S.

I could go on and on in the American context about perpetual war or predatory financialization and so on. People must notice but what can they think or do?

What has destroyed political capacity? I submit that it is in large part effective narrative propaganda and sustained demolition of most institutional bases for mass, popular political organization.

Feral Finster

I have been poor, a starving barn cat fleeing for my life. Now I am relatively well off, part of the 1%, prowling a large territory well stocked with rodents, songbirds, comfy spots for naps, and ample pussy. I now know that territory well. We’ll see how long it lasts.

I cannot say that I am any smarter than I was when I was desperate. I may have grown more cunning, more pragmatic, more sure of myself, knowing what I am capable of, which rules are made to be ignored and which rules cannot be broken. I certainly have not become more moral in the meantime. Oddly enough, I was as doctrinaire a conservative as one could get in those days.

I’d like to say that whatever success I enjoy is the result of smarts, hard work and good old fashioned grit. Honestly speaking, it was as much a matter of luck and of always keeping my eyes out for the main chance as it was anything else. I suppose I knew that giving up was not an option, not while my stomach was growling.

NR

https://www.epi.org/publication/usa-lags-peer-countries-mobility/

This article from 2012 says U.S. social mobility is pretty bad, though not quite the worst (it was a bit better than the UK at the time). It’s bad enough that I think your point stands, though.

Eddie

Did anyone else have Pulp’s “Common People” playing in their head while reading this?

mago

If you’re poor in the USA you may be resentful and embittered, and you may buy into the propaganda and blame yourself. Either way, you’re unlikely to find solace or solidarity in a community of other poors.

I’ve been broke in Spain, but had a village to keep me going. I found stoop labor in the fields working ten hours a day under the hot sun for $27 daily, thus enabling me to repay the shop keepers and merchants.

I’ve been broke in Latin America without prospects or any way home and those with little shared what they had until I could get a foot up again. People were glad to share.

These experiences and others helped shape my sensibilities. At age twelve I laid irrigation pipes in bean fields. At fifteen I washed dishes after school and on the weekends and did so throughout high school.

When I graduated to university—the first in my family to do so—I supplemented my library work study income by dealing pot. An aspiring working class writer, artist and entrepreneur, I never looked back.

It was by chance not choice that I became a chef. Hey, everybody’s got to eat, no? All right, breatharians excepted.

I still cook and feed people, but not for money anymore. That’s long gone. I’d feed the poor and their dogs if the situation arose, but there’s no fucking way I’ll feed anyone who could afford to pay me for it. Not to be too crude about it but that class can eat shit as far as I’m concerned, although maybe Feral Finster could be an exception. I’d have to think about it.

mago

Furthermore, I never gave up in the face of adversity. Never played the victim card, never cast blame no matter how bleak the circumstances.

And it’s easy enough to say to a white guy who doesn’t live in a war zone or a homeless camp by a toxic dump, what do you know about adversity?

It’s all relative in an illusionary world. Small comfort that when you’re hungry, truly hungry and not knowing when or what you’re going eat again. Just saying as the tides wash sand away from beneath our feet.

NGG

As the wealthy continue to ignore the needs of what – 80% – pick a number, it will result in a reaction against the ongoing drift of wealth to the 1-2%. This will result in a backlash against the rich. And I do mean a severe backlash. I see this as inevitable, leading to increasing social / demonstrations/ unrest. What astounds me most is that the rich can’t see how much their greed is hurting the majority of the country. Increasing profits on the backs of those who can least afford it. And those living from paycheck to paycheck will not even be able to afford to keep their health to keep working. Ain’t Capitalism on steroids Grand!

vmsmith

See William Greider’s 1993 book, “Who Will Tell The People?”

different clue

Some jobs are inherently shitty. Counting sewage at the sewage factory is going to be a shitty job. But if it paid well, including a pain-and-suffering premium for being so shitty, then the people counting sewage down at the sewage factory could at least have an okay life off the clock.

I wonder how people would respond to the slogan: ” Shitty jobs at good wages.”

Ian Welsh

An OECD study from 2008 found higher mobility is Britain.

OECD Countries” by Anna Christina D’Addio, which appeared in the OECD Journal: Economic Studies (Volume 2010/1).

It found IGE (inter-generational income elasticity) to be .47 in the US, and .41 in the UK. Lower is better, the higher the number the more children’s future incomes are related to their parents income.

That study was published in 2009, and is probably what I was going off of. You can find it here:

https://www.oecd.org/social/labour/49849281.pdf

Mark Level

1st, thanks to Eddie for the “Common People” reminder, I turned multiple friends onto this song at one time. (I esp. enjoy the William Shatner cover, it’s one time his over-theatricality perfectly melds with the vehicle.) It was interesting who got it, surprising how many didn’t, I guess ‘coz they had no experience with that situation.

I had to throw away my upper-middle class card out at age 19 and attend the School of Hard Knocks, after dropping out of college. My father had threatened me with institutionalization for not being a conformist with his generation’s standards, little did I know that he had no such power (I smoked weed sometimes, but there was nothing wrong overall with my mental health, my sense of social alienation was well-tuned to the milieu I grew up in.)

It took me a couple years to get beyond shitty blue-collar jobs where I barely kept my head above water to better service jobs and then I was able to return to college a much better-rounded person when I was 24.

I had Ian’s experience once of applying for work at a McD’s and being refused, rightly, for being “overqualified”. It happened when my insane girlfriend had gotten annoyed after I got back from my 6 month sojourn in Central America and it took me about 3 weeks to get a job again. (I was lucky, she treated her next boyfriend far worse, chased him out of the shower at knife point, he was naked. She was truly unhinged.) I was homeless-adjacent and couch-surfed for a week. Only spent like 2 nights out in the open, wide awake, an older friend got me a spot house-sitting for his friend, and when I went back to my former place of employment for a reference, my old job was open and I was immediately hired back. A low point was when I was at the local free church feed for the poor, some gnarly old dude had seen my situation and invited me back to his “place”, wanted some kind of sex I’m sure. I’d seen enough movies about serial killers, so I demurred.

I wish I had mago’s skill of reaching out for social support and getting it reciprocated that readily, I lacked that almost entirely. (Ok, my buddy hooking me up with house-sitting was one exception.) My parents were Silent Generation super-strivers, both badly aspired to WASP status and couldn’t attain it. WASPs ruled when they were young. My dad made a lot of money but couldn’t join the right Country Clubs because his Irish mom would’ve killed herself if he joined a Protestant Church. My mom was dark-skinned, Spanish-Sardinian, and very ashamed of it.

They raised us (2 siblings + me, I was the oldest and took the brunt) to be super-organized and hard-working. Thus even as an unemployed 19 year old sometimes stoner I always showed up at work, gave it my all, at least for awhile until some boss pushed me to revolt. Walked off a couple of different jobs as emotionally my self-respect was too much to eat shit and suck it up.

I thank NR for the chart, I think we all know that post-Millenials, all the younger cadres are economically doomed. At least in the early 80s I could mostly always have a roof over my head, go to bars and meet women and get laid. These poor suckers are, unless they have a wealthy family, pretty well-fucked, in the bad sense. Thus you have bitter Incels becoming fascist youth, living in mom’s basement if lucky. Women are a bit luckier in that group, except that lots of the men are angry, socially inept Incels (subject of a recent Ian thread I didn’t comment on.)

I have never been as entirely desperate as Finster (I had the option of turning down the leering old man who could’ve been a serial killer), I think he has shared he works in tech. It is nice when those of us who’ve been thru the wringer keep our lefty alienation and suspicion of authority. It certainly helped me when I finally settled down to work in secondary education in my early 30s and the schools I worked in went from friendly, supportive community institutions to deliberately dysfunctional, corporatized, drill-and-kill Fordist Satanic Mills run by sadistic, wacko administrators who mostly thought an admin degree made them a member of the 1% Elites. If we hadn’t had a Union where I worked, I and many others never would’ve survived. My union activism made me a target at times, but also gave me the sword and shield (metaphorical) I needed to survive.

Some people have it even worse of course. As I finish writing this “Makes Me Wanna Holler” came on the radio stream. The young poor in the pool room in “Common People” at least had white skin to grant a bit of status and employability.

Late Neolib Capitalism is an abbatoir that maims or slays many. There’s nothing noble in poverty, I learned that early, but it does train one well to avoid sentimentality or being gulled by con-artists. Of course settler-colonialist marauders worked very hard to exterminate Native peoples who shared resources, it wasn’t just racism, that lifestyle could not be allowed as an example. See Ayn Rand’s doctrine, she does not classify Native Americans as subhuman due to race or caste, it is because they had no “Market” in the Western sense.

And thus here we are, where we are.

Feral Finster

@mago: “Not to be too crude about it but that class can eat shit as far as I’m concerned, although maybe Feral Finster could be an exception.”

Don’t worry about me.

Anyway, to amplify mago and Mark Level’s points – a Polish dude I know was bitching about Native Americans and their cultural propensity for sharing (if I may grossly overgeneralize, Poles are some of the most Kool Aid guzzling supporters of the current order that one can buy without a prescription). That was why they were poor, see?

I told said Pole that, under the circumstances of Native culture, a sharing economy makes perfect sense. You’ve got no safety net other than your family and friends, your tribe, if you like. Money is scarce and fortune is fickle. There are no reliable stores of capital.

You may be rolling in wealth, then you get hurt and can’t work and you may be reduced to begging for the foreseeable future. Best not to burn too many bridges, you may need the help sooner than you think.

I’ve thought something similar about India (as in “Bharat”) and its culture of dowries and weddings. The average frustrated Desi is desperately short of capital, it’s not as if the banks in India are lending to the likes of him, and a dowry is one of the few available ways of pooling resources and raising capital. The wedding shows the family what they are getting for their contributions.

Of course, that also makes it harder to get ahead. One family member enjoys a streak of good fortune and there will be a host of relatives wanting help in one form or another. It makes sense – they are getting part of their investment back, so to speak.

Ergo Sum

The latest study about the intergenerational income mobility had been published in July 2025, by the Word Bank Group:

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/a6bff8fc-080f-46f2-9028-4bd93e3d0e2b

Quote from the link above:

“To illustrate the magnitude of cross-country variation in income mobility levels across countries, consider two fathers, one earning twice the income of the other father. All else being equal, the son of the higher-income father can expect to earn 50–70 percent more than the son of the lower-income father in Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Indonesia, China, and the United States.”

different clue

For people who feel little hope of personal advancement or improvement where they are at, there can still be a hope of getting revenge. One tiny little person can only get one tiny little bit of revenge. But if a million tiny little people got a million tiny little bits of revenge, that would be a whole heaping helping of vengeance; especially if all delivered to the same target.

Here is a reddit video by the Illinois Secretary of State. He had been made aware of certain sorts of outlaw scofflawry practiced by the scofflaw outlaws at ICE. He made a video about what his Department is doing in response. He invites the good people of Illinois to “call this number” for every incidence of this particular outlaw scofflaw activity ( changing license plates on cars) perpetrated by ICE personell.

” Illinois Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias Issues Warning on License Plate Tampering, Launches Reporting Hotline

ICE Posts”

https://www.reddit.com/r/illinois/comments/1odp4js/illinois_secretary_of_state_alexi_giannoulias/

Revenge is a dish best served over and over and over again.

different clue

If you can’t make things better for yourself, you can at least make things worse for people above you and against you at those rare times where opportunity meets attitude.

” Chicago, IL: Border Patrol Chief Gregory Bovino personally joined an ICE raid at a laundromat in the city, but the owner locked the doors and refused entry, halting the operation on site ”

https://www.reddit.com/r/illinois/comments/1oec6s5/chicago_il_border_patrol_chief_gregory_bovino/

different clue

I am not reallly sure where to put this comment and what it links to. Several posts ago Ian Welsh noted that President Trump and the Republican Party and the Maga movement had succeeded in destroying solidarity in America.

This youtube video, once again made by an African content-aggregator with chunks of American-made video, is addressing the impending shutdown of SNAP-Food Stamp benefits as a consequence of Trashy Trump’s and Grindr Mikes Federal Government Shutdown. Most of the videos sampled and re-webcast are either schadenfreudian or vengeful or both. Some would say that these commenters are all nasty people. I would say that it shows the extremes to which these commenters have been driven by the organized Christianazianity and KlanMaga aggression directed against the sort of people who are now making these comments.

“Magas in shambles after finding out they aint getting Snap either but celebrated BlkPp loosing their”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBeY5rbLkZg

different clue

In line with the comment I offered just above, there is this very short and very sweet little one-panel post originally from blackpeopletwitter.

” A new MAGA poll is being taken”

https://www.reddit.com/r/BlackPeopleTwitter/comments/1ofebaq/a_new_maga_poll_is_being_taken/