Jordaens Allegory of the Peace of Westphalia 1648

This is the second in a series of essays on Russia, war, grand strategy and history.

Diplomacy is the politics of anarchy.¹ Grand strategy usually manifests itself through diplomacy, but in failure, as Clausewitz instructs us, war. I wave this semaphore to avoid confusion by opening a discussion on Russian grand strategy with an overview of diplomatic history. No longer a superpower, the United States is now a great power primus inter pares. The US, no longer able to dictate the politics of anarchy must learn to appreciate the rising risk of general warfare among great powers. Such a conflict is now probable before my generation shuffles off our collective mortal coil. Maybe next year, maybe in twenty. But facts are stubborn and China has superseded the United States in all but two or three of the most important measures of economic and military power.

We live in a revolutionary diplomatic moment. First, the eminent collapse of the global diplomatic order created by Kissinger and Zhou En-lai with the Shanghai Communiqué in 1972 is, if not already dead, dying. America’s perplexing abandonment of the triangular diplomacy§ that kept the then Soviet Union and its successor state the Russian Federation and China closer to the US than to each other, has further eroded the global balance of power out of America’s favor. The American grand strategy of the 20th century—prevent any single power or coalition of hostile powers from dominating the Eurasian landmass—has been surrendered to a 21st century foreign policy of cobbled together, ill-thought out and impulsive moves, engineered by small-minded think tank ideologues and the little men of domestic politics hoping to ‘make America great again.’ I doubt three out of hundred Americans understand how seriously we torpedoed our own power by abandoning a successful grand strategy in favor of limited ideals like the “dual containment” of rogue states or the policy to fight “two and a half wars” simultaneously as Madeleine Albright’s “indispensable nation” during the Unipolar Moment of the 1990s. But, denial is not a river in Egypt and so Thucydides’ trap∇ patiently awaits an irresponsible United States like a Praying Mantis.

Chou En-Lai and Henry Kissinger enjoy a moment of levity in 1972.

Great power wars within the Westphalian system run in hundred year cycles.∅ The end of the Thirty-Years War in 1648 inaugurated the Westphalian world. Roughly a hundred years later the War of Austrian Succession begat the Seven-Years War, the first truly global war. The Treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg were signed in 1763, but left open more questions than the wars resolved.

Open diplomatic questions have a nasty tendency to war. Such were the misunderstood results of the 1763 peace, like the American struggle for Independence, arising out of England’s near bankruptcy. A reinvigorated French naval challenge to England and the domestic forces unleashed by French support of American independence attenuated the natural hundred-year gap between Great Power wars. These unintended consequences lit the French Revolutionary fuse that erupted in 1789 and ended in 1815. A renewed hundred-year gap ended with the Miracle on the Marne in September 1914. This Second Thirty-Years War, fought to settle Germany’s place in Mitteleuropa, ending in 1945 is a complete historical epoch. Taking the end of WWII in 1945 and subtracting the present year 2024 gives us an interval of 21 years in which the global balance of power continues to shift out of America’s favor and into China’s.

Chimpanzees and humans share a lot more than 98.8% of their DNA.

The balance of power is not some recondite or esoteric construct. It is a crucial gauge of power relations in an anarchic system. But it is a lagging indicator. Indeed, when the balance of power is re-established after wars or significant diplomatic denouements (e.g. the reordering of the European alliance system after the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 or the combined effects of the Nixon-shocks that unraveled the post-WWII financial settlement of Bretton Woods in August 1971 and the subsequent rearrangement of the global order with the Shanghai Communiqué in February 1972) the results simply confirm what existed beforehand. The démarche or war confirms pre-existing facts on the ground, not as most believe, create new ones. Need I remind anyone of Dick Cheney’s Baudrillard-like post-modern comment on the Iraq war when he said, “we make the reality.” No, Dick, actually you do not. We lost in Iraq. But poor Dick’s limited horizons could not conceive that the politics of war are older than humanity itself. Our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees—not bonobos— play at politics identically. “[Primatologists have] concluded that rather than changing the social relationships, [chimpanzee] fights [and wars] tended to reflect changes that had already taken place,” remarks Lawrence Freedman in his book Strategy.”† A brilliant, if depressing, observation on the human condition.

Russian grand-strategy under Putin’s twenty-five year tenure has been quadripartite in nature. First, quash any and all separatist movements or insurgencies within the internationally recognized borders of the Russian Federation—to prevent a Soviet style dissolution of the entirety of Eurasia. Second, place all of Russia’s vast resources under the umbrella of state control. Third, subject to the completion of aim number two, Russia sought neocolonial controlling stakes over the vast majority of resources within the previous borders of the USSR—know as the Near Abroad. Putin’s fourth aim is to secure a non-NATO buffer zone, or sphere of influence, to the south and west large enough to keep Russia safe from invasion from those two cardinal points.

Brezhnev says to Nixon, “did you hear that?”

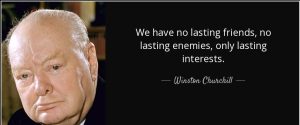

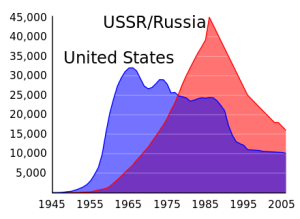

Of course, nuclear weapons do form a part of Russian grand strategy but they are a separate problem understood best within the context of the late 20th century arms control regime created by Nixon and Brezhnev, affirmed by Reagan and Gorbachev, and enlarged by Bush the Elder and Clinton with Yeltsin. For now, prudence dictates we proceed under the precondition that any war Russia fights will be conventional, that is until its existential interests have been breached. Adjacent threats are not direct, but there can be no denying (not-so) covert NATO, sorry, I mean Ukrainian attacks against Russian ballistic missile early warning radars are provocative in extremis. The Ukraine is not a nuclear power and without need or interest in destroying such radars. It’s NATO action.

Full stop.

Shrewd Putin shows more restraint than any contemporary Western leader possesses.² Just look at Macron flailing wildly about France fighting Russia—its historical ally! Or Polish President Andrzej Duda agitating direct NATO war against Russia. Sure, its lunacy but rational lunacy in a Polish context. But, with every new report of NATO, so sorry, I mean Ukrainian, skullduggery my sphincter tightens and I look to build a bomb shelter.

On 9 August 1999 Russian President Boris Yeltsin named then unknown Vladimir Putin as his prime minister. In September a series of apartment bombings, attributed to Chechen separatists, in Moscow and Volgodonsk killed over 300 people.‡ Most observers, including myself, believe this was a false-flag operation. Whatever the case, it succeeded in galvanizing the Russian people in advance of the Second Chechen War. Putin quickly eclipsed Yeltsin as president of the Russian Federation on December 31, 1999 and subsequently ordered the bombing of Grozny. Putin pursued the Second Chechen War with ruthlessness right up to its official non-official ending in 2009. For ten years Russia showed no mercy, raining destruction and death on Chechen town and village, combatant and civilian alike.

“Let them eat cookies,” Nuland says the Ukrainian Banderites.

Why? Because the consequences of failure were so grim, not just for the Russian Federation, but for the world. Herein lies a significant failure of American imagination. Try and visualize the chaos of a rump Russian state ending at the Ob River and a dozen more sovereignties existing across Eurasia. The resulting power vacuum and disruption to the balance of power would have made the Balkans look like a Sunday picnic. Make no mistake, this is the terminal goal of former Undersecretary of State for Revolution and Chaos, Victoria Nuland, wife of neocon éminence grise Robert Kagan, should the Ukraine prevail. It’s insanity equivalent to opening a can of baby sand-worms from Arrakis in the Gobi Desert just to see what happens. Neocons, like Nuland, suffer from what I call khaophilia, from the ancient Greek meaning love of chaos. They are rubberneckers on the interstate whose stupidity cause mass pileups. Or as my Turkish buddy Murat said one gorgeous spring day of a young ne’er do well on the streets of İstanbul, “he has an uncontrollable desire to throw rocks at hornet’s nests and watch what happens.” Think Libya. But I digress.

The second arc of Putin’s grand strategy was complete within four years of his accession and election to the Russian presidency. By 2003 he had dissolved every independent media outlet and stripped all but the most dangerous of oligarchs of their power and assets, exiling many. He reserved the most severe punishment for his most serious and worthy opponent, Mikhail Khodorkosky. At the time Khodorkovsky was worth an estimated $15 billion USD and was CEO of Yukos, Russia’s largest oil and gas company. Putin had his assets seized by and incorporated into the state oil company Rosneft. Khodorkovsky was jailed on trumped up charges of tax evasion and convicted in 2005. Russia’s vast national resources were now under the control of the государство—the state.

The third goal of his grand strategy was decidedly neocolonial and took longer to achieve. However, by 2016 when I visited all but one of the Central Asia republics (Tajikistan) the resources of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, a goodly portion of those in Kazakhstan (reliably pro-Russian), and Kyrgyzstan appeared under the control of the Russian Federation. Russian TV news was on in the hotels and airports and every ATMs but one dispensed rubles not dollars.⊕ Only Azerbaijan gained a measure of independence, but it came at an enormous cost.

Nagorno-Karabakh region, site of Armenian aggression and occupation deep inside Azerbaijan.

From 1991 forward Russia supported Armenia’s land-grab in Nagorno-Karabakh, a de jure part of Azerbaijan, but soon under de facto Armenian control. Following the first Nagorno-Karabakh War’s end in 1994 Armenia encouraged its citizens to populate the newly conquered territory, á la Israeli settlers gobbling up the West Bank. Russia’s aim to keep Azerbaijan divided and preoccupied had salutary second order effects, like limiting the interests of western oil companies in Azerbaijan. Not until 2023, after Turkey—infuriated by Russian attacks on its jets, soldiers and interests in Syrian Kurdistan—up-armed the Azeris with modern NATO armaments, were the Armenians summarily tossed out of Azeri territory. Claims of a second Armenian genocide are without merit. The Azeris committed no crimes against humanity. They waged war against an aggressor and ejected the occupier. Hyperbole is wasted on reality.

An orderly and peaceful exodus of illegal occupiers from Azeribaijani territory. Not genocide.

To Russia’s satisfaction the Transcaucasian nations remain divided. Azerbaijan, a Shi’ite nation, schizophrenically looks to both Iran and the US for guidance. Armenia, unwilling to accept defeat, choses selective outrage. Meanwhile an economic and demographic time bomb of its own making prepares to detonate. Then there is poor benighted Orthodox Christian Georgia. I recall sitting in Alex Rondeli’s Tbilisi office in 2003 discussing the future of Georgia and the possibility of joining NATO. This was in the immediate aftermath of Sheverdnadze’s ouster, the Rose Revolution, and Columbia University educated Mikhail Saakashvili’s presidency. Rondeli, to his credit, percolated ambivalence about NATO and American power. I perceived him as much more the pragmatist than romantic, as such terms relate to power politics. But his associate, one Timur Iakobashvili, was a strident true believer. He waxed poetic about America’s invasion of Iraq. He hectored me about our success at expeditionary warfare—the insurgency had yet to begin. And he was certain NATO would come calling.

“No, it won’t,” I said, “plus, á la perfide Albion, America will betray you the moment we lose interest in your part of the world.”◊ I fancy I got the last word but Iakobashvili got the Ambassadorship to the US.

Georgia divided.

Regardless, Abkhazia and Ossetia were shaved off of Georgia in the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. The nation, divided still, demonstrates the principle of divide and rule is as effective now as it was when the Hittites disastrously invaded Assyria in 1237 BC. Fortunately, most Georgian citizens have begrudgingly accepted this modus vivendi with the Russian Federation, much as Mexico accepts the giant of el Norte. Sometimes there is no choice. Sometimes you have to make the best bad choice. That’s the national interest in an anarchic world. Obviously, this suits Russia just fine, having the added benefit of a divided Georgia aligning with Russia’s interest in preventing NATO accession.

That brings us to the present moment. The matter at hand. Putin’s fourth and final grand strategic aim: carve out a large enough buffer between NATO and the Russian Federation that makes the costs of invasion from the south or west prohibitive. As I have shown, the Russian way of war is predicated on three easily comprehensible strategies. First, scorched earth tactics and the suffering of the Russian people.° Second, the ability to ‘spin up,’ recognize and promote learning generals while under distressing clouds of бардак—messiness.ƒ Finally, what has been left unsaid but demonstrated clearly in the three wars cited in my previous essay, is the Parthian, or steppe way of war: strategically trading space for time.

the Battlefield of Carrhae, where Crassus and his legions met their doom. Authors photo.

The Scythians first did this to Darius I of Persia in 513 BC, luring him ever deeper into the Pontic Steppe. The Parthians destroyed Crassus and his legions in 53 BC at Carrhae by trading space for time, suckering him down from the watered hills around Edessa onto the parched plains of Mesopotamia. The Seljuk Turks conquered half a world with such tactics first at the Battle of Dandanaqan in 1040 AD against the Ghaznavids, then at Manzikert in 1071 against the Byzantines. The Mongols won the greatest empire humanity has ever known on the backs of their horses, deep in the steppe, firing recurved bows. Even Tamerlane, scion of the Chingissid line and first of the gunpowder kings, defeated the Ottoman Sultan Yıldırım—the Lightningbolt—Bayezit at the Battle of Angora, leaving him to dash his brains out in a gilded cage as the Great Emir trudged back to Samarkand. Grant and his successors would call it the strategic defensive. This, combined with scorched earth tactics gives Russia enough time to marshal all her resources to mount a successful counter-offensive, as she did at Poltava, Borodino, and Stalingrad. The Ukraine (and Belarus) is simply the space Russia will trade for time.

Seljuk cemetery near the battlefield of Manzikert. Authors photo.

It is important to recall that all Russia asked of the Ukraine, before the war began, was neutrality. But the Brits suckered the Ukraine’s Comedian-in-Chief into fighting against Russia as a cat’s paw for NATO. Whiskey tango foxtrot!

So now Russia destroys the eastern part of Ukraine, not to conquer, but simply preserve a large enough buffer so that any would-be invader can be met in Russian time, not invader time, and whereby be destroyed. Space for time has been and will remain the single most important and historically relevant aspect of her grand strategy, barring a nuclear exchange and even then, who really knows? Russian Eurasia is vast. Space for time is a vital interest to Russia. Victorious, she will dictate the peace, annex all Ukrainian territories in a line from Sumi in the north through Poltava, Dnipro on the east bank of the Dnieper River, Zaporizhzhiya, then south across to Kherson, Mikolaiv and finally the entire Oblast of Odessa. What will remain is a landlocked rump, near-failed Ukrainian state ruled by a corrupt Comedian-cum-Dictator, dependent on Russian good-will. Sovereign neutrality versus suzerainty? I know what I would have chosen.

“что делать?”ξ What happens after Russia defeats the Ukraine? What of her increasingly tight-knit energy for cash rapprochement with China? The Russians have clearly entered one of their “Russians are an Asiatic people” phases that cycle through the Russian intelligentsia every few decades like a recurrent case of giardiasis. Does this mean we are we looking at an Asiatic version of the pre-WWI Антанта (entente)? I confess my crystal ball is getting a bit foggy.

What will an emboldened, revanchist Russian grand strategy look like? What kind of forward actions will it take? Will it revive its navy and utilize the harbors of Syria to pressure Israel and project power into the greater Middle East? If so, the results might be beneficial to peace in the region. At the very least it will piss the Israelis off. Will it revive its relationship with Egypt, Nasser-like, displacing American influence and subsidies? At risk of a two front conflict against Iran and Egypt? That might chasten the Israelis into some kind of acceptance of international norms. At the very least it’ll sober ‘em up from their decades long binge of oppression against the Palestinians. Will Russia super charge its submarine fleet in the North Atlantic? Threatening NATOs key re-supply line? Will it find a unique way to avoid war but pressure the Baltics into leaving NATO for a pre-World War One Belgian-like guaranteed neutrality? Will it support a Chinese invasion of Taiwan? There is a non-zero chance that each and all of these might happen and more. Russia has regained a decent share of the stature it lost globally when the USSR dissolved. Not all of it, however, and so she is a spoiler on the international stage, albeit a big one. Nor should she be underestimated.

And yet . . .

U.S. and USSR/Russian nuclear weapons stockpiles, 1945-2006 under the nuclear arms control regime of the late 20th century.

Of course, the majority fault lies with America. Presidents Bush the Younger, Obama, Trump and Biden foolishly drove a heavyweight continental power, former and potentially future ally into the arms of our biggest international competitor, China. I don’t know about you, but I would have preferred Russia on our side fighting the land war when the big show against China begins in earnest. With the right coalition, one including a Russian threat to China’s rear, the Middle Kingdom can be defeated. Sadly, the march of folly begun with the abrogation of the ABM Treaty by Bush the Younger in 2002 accelerated with the abeyance of the INF Treaty in 2018 by Trump, leaving the nuclear arms control regime began by Nixon and Brezhnev, solidified by Reagan and Gorbachev and expanded under Bush the Elder and Clinton, in tatters. We world citizens are left to live, once again, at very real risk of nuclear annihilation. What a shame small minds presided over such potential.

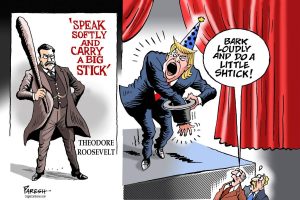

Obviously the horizons of American diplomats have never been very far or wide. Certainly not enlightened enough to embrace or understand men of foresight like Teddy Roosevelt, Henry Kissinger, and James A. Baker, III. After all, banality of banalities, the business of America is business. Let’s have featherweight Warren Christopher be our Secretary of State! How about Madeleine Albright or even cage-match Condi? Anthony wet-Blanket anyone? Such choices leave me disgusted.

Obviously the horizons of American diplomats have never been very far or wide. Certainly not enlightened enough to embrace or understand men of foresight like Teddy Roosevelt, Henry Kissinger, and James A. Baker, III. After all, banality of banalities, the business of America is business. Let’s have featherweight Warren Christopher be our Secretary of State! How about Madeleine Albright or even cage-match Condi? Anthony wet-Blanket anyone? Such choices leave me disgusted.

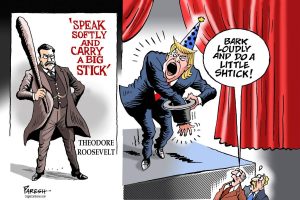

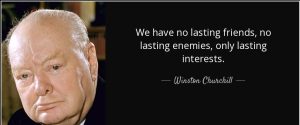

What’s even more dangerous is American worship at the ‘Church of the Divine Belief in the Steadfastness of Our International Friends’. Does it have a pope? How many brigades does he have? Alas, nothing is sillier or more dangerous than such blind adherence. Our European allies are freeloaders, sipping their cafe au lait under an America tax-payer financed security umbrella while the sun sets on Western Civilization. Don’t misunderstand me, I get Europe’s reluctance to rearm and/or countenance war of any kind after the catastrophe of the early 20th century.

But, folks, let’s get real for a moment and recognize truth.

No nation has steadfast friends. Nations have only implacable, insatiable interests. When those interests align, you get harmony. When they do not, you get conflict, revolution or war. This is the way of the Westphalian system, established in 1648 and now global in scope. We fool ourselves trusting the panacea of international law and/or a rules based order.

No nation has steadfast friends. Nations have only implacable, insatiable interests. When those interests align, you get harmony. When they do not, you get conflict, revolution or war. This is the way of the Westphalian system, established in 1648 and now global in scope. We fool ourselves trusting the panacea of international law and/or a rules based order.

In Westphalia there is only anarchy, self-interest and impermanent security. For if one nation has absolute security, then all others are absolutely insecure.

¹: In the Westphalian order there is no mutually agreed upon global government or mechanism with a monopoly on violence to enforce peace. There is a word for this: anarchy.

§: The Wikipedia entry on Triangular diplomacy is 85% rubbish and 15% cherry-picked quotes. The concept behind triangular diplomacy is simple, to paraphrase Kissinger: keep relations with our peer competitors closer to us than they are to each other. The Wikipedia entry is a self-fellating perversion of the original concept. Donald Trump wouldn’t know triangular diplomacy from a parallelogram, nor would Anthony Blinken.

∇: The Thucydides trap, a phrase coined by scholar Graham Allison, pertains to the challenge of a rising power opposing the defender of the status quo and the resultant breakdown of diplomacy, then almost universally followed by great power general warfare. For example, Athens rising, Sparta status quo. United Kingdom status quo, Germany rising. Dozens of other examples exist throughout history.

∅: It is crucial to note that I am discussing warfare and grand strategy within the Westphalian system, a system that now dominates the globe. There were plenty of devastating wars all over the world between 1648 and 1900. But, generalized global warfare under the Westphalian system is materially different and not all state actors were apart of the Westphalian system until the 20th century.

†: Freedman, 2013, p.4. I’d further highlight that chimpanzees and bonobos are the Yin and Yang of mankind’s warring sides.

²: this essay was written before NATO forces, French, Polish and Ukrainian made their incursion into the Kursk Oblast of Russia, which makes my comments even more appropriate and predictive.

‡: It’s September of 1999, I don’t recall the exact date, but it was around 11:30 pm or so, I was sitting in the original Moscow McDonald’s on the corner of Bronnaya and Tverskaya ulitsas. In 1999 McDonalds was still a status symbol to Russians so I humored my business associate, Volodya, with a Биг Мак. The moment we sat a boom rang out, followed by rattling windows and the soft shaking of the building. An earthquake in Moscow? Everyone except me hit the floor. The immediate danger gone, we all went outside looking up and down Tverskaya ulitsa. To the southeast a column of smoke rose, barely visible behind the Kremlin floodlights atop the Trinity tower. Volodya turned to me and said in Russian, “those fucking Chechens are all going to die now.” He was not far off the mark.

⊕: The sole holdout was an ATM in Osh, Kyrgyzstan that spit out Chinese Yuan. What do you think that presages?

◊: La perfide Albion, French for Perfidious Albion refers to the diplomatic treachery of England. And yes, I really said this to him. I would also note Scott Ritter made virtually identical comments about Georgia in a podcast yesterday. Fast forward to the last seven minutes.

°: “Shonik, don’t worry about us,” my Russian ex-wife used to say, “we’re used to it. We’ll endure.”

ƒ: Thank you reader ‘j’ for this wonderful concept.

ξ: “What is to be done?” Vladimir Lenin, Saint Petersburg, 1902.

Kelley lives in San Antonio, Texas. He has a Bachelor’s degree in European History, and two Master’s: International Relations and Political Economy and another in History, focusing on the medieval trade routes of Inner Asia.

So, Democratic Socialist (ie. has politics a 70s liberal would have agreed with, but is less racist) Zohran Mamdani has won the nomination as the Democratic candidate for New York City Mayor.

So, Democratic Socialist (ie. has politics a 70s liberal would have agreed with, but is less racist) Zohran Mamdani has won the nomination as the Democratic candidate for New York City Mayor.

What strikes me is our loss of leadership competency, from the extremely competent people who managed us through the depression and through WWII to the clowns of today.

I’ve been involved in Youtube exchanges where some idiot creates a video claiming how we “saved” the USSR in WWII via Lend-Lease. First, that is that factually untrue. The USSR saved itself; Lend-Lease was such a trickle in 1941-1942 that it had essentially NO effect on the Battle of Moscow in December 1941, and very little impact on the Battle of Stalingrad in the fall-winter of 1942. Stalingrad at the very least marks the point where “the USSR will survive and not lose” so Lend-Lease didn’t “save” the USSR. Lend-Lease did help the USSR, but the bulk of it (60 %) came in the last 10 months of WWII well after the USSR had turned the tide and driving back the Wehrmacht out of the USSR. The most important part of Lend-Lease help wasn’t the weapons we sent, nor the locomotives, nor the steel, nor the petrol, nor even the trucks (the most common ‘fact’ brought up). It was the food we sent–in 1942 42 % of the USSR’s arable land was occupied, and the USSR instituted a rationing program where soldiers, workers in essential industries, and children got first priority on food. If you weren’t one of those, you didn’t get much, and hunger contributed mightily to the USSR’s civilian death rate in the war. The FDR administration promised the USSR 10 % of US food production to help, but could only manage to deliver 3 %.

But my point in mentioning Lend-Lease is that such Youtubes miss the main reason why we did what we did in aiding the USSR. It wasn’t some act of friendship or mercy, we weren’t just ‘being nice’; we did it OUT OF ENLIGHTENED SELF-INTEREST. George Marshall and the US military leadership were not sure we could win WWII without Soviet help; at the very least if the USSR went down to defeat and Hitler obtained access to the USSR’s resources it would prolong both the length and sacrifice of the US and UK. The military problem the US faced was war both in Europe and the Pacific, with far-flung bases and long supply lines that “ate” up manpower and required a powerful Navy and Air arm to protect. We thus couldn’t raise an army of hundreds of divisions and supply it overseas, to do the work that the Soviets were providing the West by grinding up the Wehrmacht. Keeping the Soviets in the war was quite vital; ergo Lend-Lease.

In short, Marshall and his ilk had a clear and correct notion of what the US could do, and what it couldn’t do. The manpower restrictions on ground forces meant “no land war in Asia” which meant we wouldn’t field armies in China. Instead, we focused on a ground force manpower-minimizing “island hopping” strategy where we only took relatively few key islands and just left Japanese ground forces in elsewhere stranded and cut-off from supply. The bulk of the ground forces we did raise were going be used to defeat Hitler, whom Marshall correctly identified as the biggest threat to the US, given Germany’s technological skills and industrial base.

This kind of calculation is what we’ve lost. In WWII, we knew we were powerful, in some ways relative to the world more powerful then than now, but we knew we couldn’t do everything and that we shouldn’t even try. But after WWII, inside the US spread the notion (largely spread by conservatives and the anti-communists) that we had really ‘done it all’ and won the war without much of anyone’s help. Why did we cave to Stalin at Yalta? Why didn’t we let Patton drive the Soviets out of Eastern Europe? We had the bomb after all! (cue in Henry Stimson rhetorically patting his coat pocket). WE WERE OMNIPOTENT!

The first generation who acted on this belief, a belief definitely not shared by those who planned and executed WWII, was the “Greatest Generation” who had fought it as common soldiers when they assumed leadership—JFK through Reagan/Bush I. It led to Vietnam and to interventions everywhere, because we could and should impose our will upon the world. It was exacerbated when (as you say) financial means of scoring economies replaced measures of actual industrial capacity and output, from Clinton to today. What gets me is that the US’s leadership is more arrogant and more convinced of its supremacy despite the fact by all objective measures, whatever power the US actually has is far less relative to the rest of the world than the US during WWII during Marshall’s and FDR’s time. Yet Marshall and FDR knew we weren’t omnipotent and couldn’t ‘do it all’. And I fear nothing less than a massive comeuppance will change their attitudes.

(This blog is for understanding the present, making educated guesses at the future, and telling truths, usually unpleasant ones. There aren’t a lot of places like this left on the Web. Every year I fundraise to keep it going. If you’d like to help, and can afford to, please Subscribe or Donate.)