So, Trump has decided to raise tariffs on India to 50% (who knows if he actually will), over their imports of Russian oil. Meanwhile:

Senators Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, and Connecticut Democrat Richard Blumenthal are the lead sponsors of a bipartisan bill which would impose primary and secondary sanctions against Russia and entities supporting Putin’s aggression if Moscow does not engage in peace talks or undermines Ukraine’s sovereignty.

The bill includes imposing 500-percent tariffs on imported goods from countries that buy Russian oil, gas, uranium and other products.

At this point all smart nations and blocs should be doing their best to reduce vulnerability to the US, to route around it and to move towards as much autarky as possible.

It’s notable that while China remains a huge trading power, the #1 economic priority over the last eight years has been making all major industrial stacks domestic: ending their need for industrial goods from other countries and reducing their need for imports of resources. Where that’s not possible, they have shifted to reliable partners like Russia and Iran and various other nations in Asia, Africa and South America.

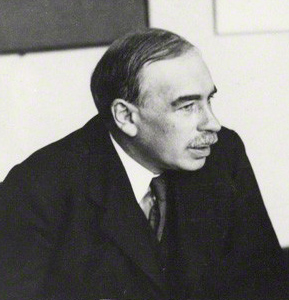

John Maynard Keynes was of the opinion that anything a country needed, it should make or grow at home if at all feasible. Price arguments are largely ludicrous, because if you don’t have vast exposure to trade or need to buy important goods overseas and you don’t allow significant currency movements outside your border, prices are largely a domestic matter. That is to say, they are a matter of policy. Government actions largely determine the price of goods and services produced in the country IF the country is capable of producing those goods and services itself.

Or, again, as Keynes said, “anything we can do, we can afford.” (The corollary is that anything you can’t do, you can’t afford.)

Trade dependency is foolish. It may be necessary in some cases, and certain policy choices require it, like export driven industrialization. But once you’ve got an industrial base, it becomes a choice.

If a country produces everything it needs, including reasonable luxuries, questions of employment become ludicrous. Just reduce working hours to 30 hours a week, or even 20, or institute an annual income. The idea that resources must be distributed thru jobs is, again, ludicrous. Once a society produces enough why not increase leisure? Why not encourage citizens to do art, write, study or even sun-bathe? Most people don’t have jobs they’d keep doing if they were independently wealthy. There is NO virtue to work that is not actually needed.

A trade structure which creates a vast web of interdependency doesn’t decrease the likelihood of war. The Europeans found that out in WWI: the pre-Great War world had vast amounts of trade, and it was argued that war between the Great Powers was obsolete: they would all lose massively. It was true that they’d all lose massively, and they still went to war.

All that too much interdependence does is restrain nation decision making ability, and, in democratic countries, the ability of politicians to actually do what their constituents want. (They often don’t consider this a bug, mind you. It’s nice to be able to say “we have to reduce taxes on rich people and corporations to be competitive”.)

Free trade is a bad idea for any country that isn’t postage stamp sized. If you can’t make it yourself, learn how. Trade for what you can’t grow or dig up yourself, and actually need. Eat seasonally.

This doesn’t mean “no trade”, it simply means managed trade and an emphasis on making as much as you can yourself.

Certainly no country which can avoid it should need to import food, and likewise and deep need to import energy is a huge weakness which can easily be used against you and which can lead to war. (This is the proximate cause of Japan attacking the US in WWII: America cut Japan off from oil, and they had to have it.)

This also leads back to our previous discussions on population levels and birth rates. A China with 1.4 billion people needs more imports than one with 600 billion people. An American with 150 million people is far freer than one with over 300 million.

As for defense, well, all real countries should have nukes and advanced missiles. It’s that simple. If you do, you’re a real country. If you don’t, you aren’t and are subject to easy blackmail by any great power.

Moving towards autarky is a worthwhile goal. In most cases it will never be achieved and full autarky is rarely a good idea, but getting close is.

(See also, “Ricardo’s Caveat”, because economists are wrong about comparative advantage in free capital flow systems.)

If you’ve read this far, and you read a lot of this site’s articles, you might wish to Subscribe or donate. The site has over over 3,500 posts, and the site, and Ian, take money to run.