Anthony Ruelas watched for what seemed like an eternity as his classmate wheezed and gagged in a desperate struggle to breathe.

The girl told classmates that she was having an asthma attack, but her teacher refused to let anyone leave the classroom, according to NBC affiliate KCEN. Instead, the teacher emailed the school nurse and waited for a reply, telling students to stay calm and remain in their seats.

When the student having the asthma attack fell out of her chair several minutes later, Ruelas decided he couldn’t take it anymore and took action.

“We ain’t got time to wait for no email from the nurse,” a teacher’s report quotes him as saying, according to Fox News Latino.

And with that, the 15-year-old Gateway Middle School student carried his stricken classmate to the nurse’s office, violating his teacher’s orders.

What sort of person is Ruelas?

Mandy Cortes, Ruelas’s mother, told KCEN that she assumed her son–who has been suspended in the past–was to blame when the school informed her that he had been suspended again.

… “He may not follow instructions all the time, but he does have a great heart,” she said, noting that she was now considering home-schooling him.

The boy is, in other words, a troublemaker with authority issues. Thank goodness, eh?

I imagine most readers are familiar with the Milgram experiment, where university students were told to shock people by authority figures and most did so.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing, and want more of it, please consider donating.)

I’ve always been curious what the people who refused were like, but oddly, that research did not appear to have been done.

A new Milgram-like experiment published this month in the Journal of Personality has taken this idea to the next step by trying to understand which kinds of people are more or less willing to obey these kinds of orders. What researchers discovered was surprising: Those who are described as “agreeable, conscientious personalities” are more likely to follow orders and deliver electric shocks that they believe can harm innocent people, while “more contrarian, less agreeable personalities” are more likely to refuse to hurt others.

“The irony is that a personality disposition normally seen as antisocial—disagreeableness—may actually be linked to ‘pro-social’ behavior,'” writes Psychology Today‘s Kenneth Worthy. “This connection seems to arise from a willingness to sacrifice one’s popularity a bit to act in a moral and just way toward other people, animals, or the environment at large. Popularity, in the end, may be more a sign of social graces and perhaps a desire to fit in than any kind of moral superiority.”

…The study also found that people holding left-wing political views were less willing to hurt others. One particular group held steady and refused destructive orders: “women who had previously participated in rebellious political activism such as strikes or occupying a factory.”

Most people who are popular and too agreeable do not have strong red lines. Their morality is set by authority figures and peer groups. Whatever seems okay with the people around them is okay with them.

I wrote about this in the past in my post on the Decline and Fall of Post-War Liberalism. One key part of breaking an essentially egalitarian economic order was finding and destroying the people who wouldn’t go along to get along, the people who would fight.

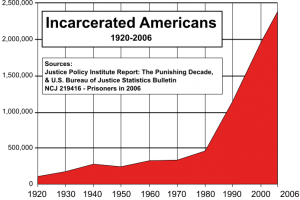

From Wikipedia

This was done by creating a set of bullshit laws: Drug laws. Consensual activity which harmed no one (especially in the case of marijuana) was made illegal.

The sort of people who wouldn’t obey rules, laws, or orders that didn’t make sense to them disobeyed those laws and went to prison in droves, where they were destroyed politically, economically, and personally. The vast majority had committed no violence.

The gut was ripped out of America’s working and lower class troublemakers.

Since then, our method of child-raising has become one of high-surveillance. “Helicopter parenting” means children rarely spend time doing anything not approved of by parents or other authority figures. Police patrol schools. Children have cell phones, allowing their parents to check on them any time they want. Houses increasingly have internal surveillance systems to keep track of children.

People who are under constant supervision with little time to be alone or to be with friends without authority supervision tend to become “go along to get along” people, unused to thinking for themselves, and used to jumping through hoops for the approval of authority. Their entire lives have been about doing so, after all.

This is especially true of our elites, and while it’s usually been truer of them than the lower orders, it has become even more so than it was in the past. You could get into an Ivy league school in the past based on pure genius and talent; today you need excellent grades, an extra-curricular record which precludes alone time, and an essay which hits all the proper, authority-pleasing conformist points.

Society does not work for everyone when it becomes authoritarian and conformist. People are what they do, to a remarkable degree. We already had a system designed to create conformity (school is nothing but a conformity producing machine: sit down, speak only when called on, and do what you are told to do in exchange for adult approval and a decent future). The system we have now is even more designed to produce people who won’t stand up when asked, frankly, to be Nazis. Or torturers (an activity of which most Americans approve).

The troublemakers are the guarantors of your freedom and prosperity. When they are are broken, both will soon follow.

They were broken. Both followed.