We’re about 3 weeks into our annual fundraiser. Our goal is $12,500 (same as last year). So far we’ve raised $8,180 from 72 people out of a readership of about 10,000.

If you read this blog, you’re usually ahead of everyone else. You know, years in advance, much of what’s going to happen. The intelligence from this blog is better than what people pay $10,000/year for. Without donations and subscriptions, this blog isn’t viable. If you want to keep it, and you can afford to, please give. If you’re considering a large donation, consider making it matching. (ianatfdl-at-gmail-dot-com).

As I write this I’m eating a sub I bought from across the street. While it was being prepared I chatted with the young woman making it, and she told me about moving from the Canadian Maritimes to Toronto, to, in essence, get a job that pays a little more than minimum wage. Because out in the Maritimes she had trouble getting even that.

As I write this I’m eating a sub I bought from across the street. While it was being prepared I chatted with the young woman making it, and she told me about moving from the Canadian Maritimes to Toronto, to, in essence, get a job that pays a little more than minimum wage. Because out in the Maritimes she had trouble getting even that.

I thought to myself that her experience is one that politicians need to have. Many politicians, of course, have never ever had a bad job. They went straight to a good university and from there to a good job or internship. They probably worked hard for it, and think they deserve what they have, never really seeing all the people whose feet were never on that road, who never had the same shot they did.

Then there are a fair number of pols, though less and less every year, who will tell you about the lousy jobs they had as teenagers, or maybe in their early twenties. But in most cases something is different between them and many working class and even middle class folks.

They knew they weren’t staying there.

When I was poor and working in lousy jobs I used to look in the mirror and see myself at 50, or 60. I expected to still be working at grindingly hard jobs, being treated badly by bosses (because there is no rule more iron than that the worse you are paid the worse your employer will treat you), and still being paid little more than minimum wage. That was the future I saw for myself.

And when I was on welfare, after having failed to find a job for 6 months, and even being turned down by McDonalds (in the middle of the early nineties recession) I wondered if I’d even ever have a shitty job again. I ate cheap starchy food, turned pasty and put on weight. My clothes ran down. When my glasses broke beyond the point where tape would keep them together I literally had to beg the optometrist to make me his cheapest pair and I’d pay him later. (I eventually did.) My life was a daily grind of humiliation.

And that’s what I expected my life to be.

When politicians participate in one of those “live on Welfare for a week/month” programs I’m happy, but I’m also dubious. The difference is that they know they’re getting out in a week or a month. They know it’s going to end. Much as I applaud someone like Barbara Ehrenreich, who lived for months working at lousy jobs, again, she knew it was going to end. She knew that, if push come to shove and she became seriously sick, she could opt out. She knew that if she really couldn’t eat for days, that was her choice.

Living without that safety net, knowing that if something goes wrong, that’s just too bad, changes you. Living without any real hope of the future, knowing that the shitty job you’ve got now is probably about as good a job you’re ever going to have, changes you.

And it changes your sense of what hard work is, of what it means to be deserving. I remember working on a downtown construction site as temp labor, and I’d watch all the soft office workers with their un-calloused hands come out for lunch, and I’d wonder why they got paid two or three times what I did for work that was so much easier (and which, of course, I could do, even if I didn’t have a BA.) At the end of the day they might be stressed, but I’d go home physically exhausted from hard labor and so would my co-workers.

Of course, I got out of that. I’d say “I went back to university”, but even though that’s true, it’s not what got me out, since I never finished my BA. Instead what got me out is that I finally got a couple chances to prove what I could do—I got a temp job in an office, and was one of their most productive workers (they measured it.) Later I got invited to blog, and hey, I can write, even if I don’t have a BA. I got lucky. Like most people who get lucky in work, that luck involved a lot of hard labor, but it also involved luck.

But a lot of folks never get lucky despite the fact that they work hard. Perhaps they aren’t really all that bright (half the population, after all, is below average intelligence.) Perhaps they’ve got some personality issues or weak social skills. Perhaps there’s something not quite right in their brain chemistry. Or perhaps they just never catch a break because they aren’t lucky and their parents weren’t well enough positioned to help them get those breaks.

But still, most of them work hard and earn their money, whether it’s barely more than minimum wage or they did get a bit of luck and got one of the few remaining good blue collar jobs.

But when they look in the mirror, they know that the guy or gal looking in the mirror ten or twenty years from now is probably going to be doing the same thing. And they know that they’re one bad break away from losing even the little they have—one illness, one plant closure, one argument with their boss.

They don’t have a lot of hope for the future, except that it won’t get worse. The life they live now is the best it’s probably gonna get.

Living like that changes you. It makes you see people differently. You understand that there are a lot of bad jobs out there, and that someone’s going to be stuck with them. You know that most of those jobs are either hard or humiliating, and often both. You know that for too many people, a shitty job where they’re abused by their boss is as good as it gets.

This all comes to mind because of how Congress and other politicians have acted throughout the auto bridge loan debate. Folks who passed a bill giving their sort of people: wealthy people who went to good colleges, who work with their minds and not their hands in the financial industry, 700 billion dollars without any real oversight wanted to force a cram down of wages and benefits on auto workers. Journalists on TV who were sympathetic to the bailout, dripped with palpable contempt for the idea of “subsidizing unprofitable companies”, something that didn’t bother them when it was soft-handed professionals like themselves on the dole.

The narrative of the GI generation was “first person in my family to go to college”. They came up from poverty, they probably expected to live in poverty all their life, but when the world changed so changed their chances.

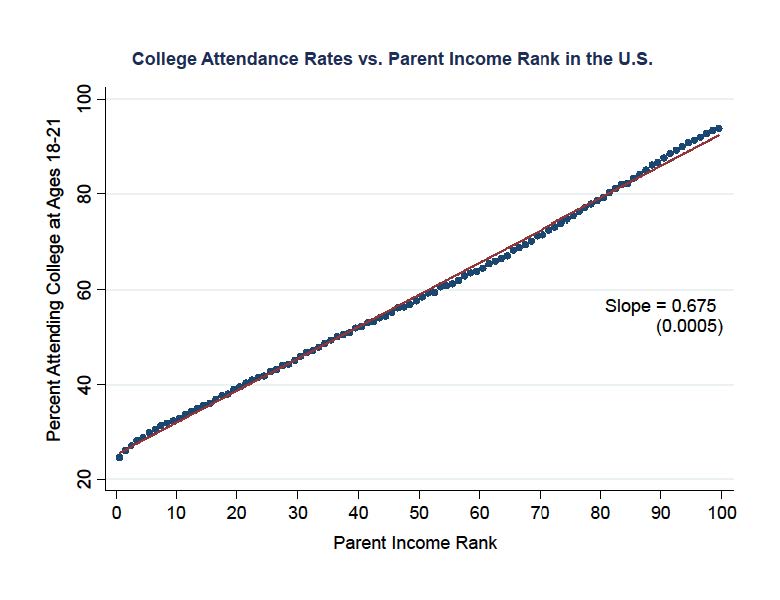

It was a generation of opportunity, but what has happened since them is the “closing of the American elite”. Every generation the odds of someone born poor making it into the elite decrease. At this point about 80% of the working class don’t get degrees. The US now has the least inter-generational social mobility in the Western world (it used to have the most). The elites have become self-perpetuating, and they never had to stare in a mirror and know that they may never have more than minimum wage job; that probably this is as good as it gets.

As a result they have no real empathy or understanding of the vast majority of the middle and working class. The elites know they worked hard to be where they are, what they don’t see is that their feet were put on the path from birth, and that every opportunity was given to them. Opportunities that were not so open to those below them, who have to virtually bankrupt themselves to go to university and whose schools were completely broken, even as the value of BA declines to multi-generational lows. Put yourself in debt for 20 years, and it may still not buy you the good life.

That existence, hand to mouth, with no hope, is something America’s elites have never experienced and don’t understand. For them there’s always another opportunity, always another chance: always hope. And what matters to them is when the “deserving”, which is to say, their own class, is in trouble. So they’ll bail out the financial sector, even though it hasn’t made any more profit than the Big 3 in the past 8 years, and unlike the financial sector, didn’t bring down the world economy, but they won’t help out the undeserving whom they don’t understand.

America has become the most class ridden society in the Western world, far worse than Britain. Congressional seats are passed on to family members and friends like corrupt boroughs in 18th century England. The rich are bailed out and ordinary people left to sink. Responsibility is enforced on the least in society while the privileged are allowed to skate. Sell a gram of pot, go to jail; but kill hundreds of thousands in an illegal war and it’s no big deal.

The elites don’t live in the same world as ordinary people. They have become completely disconnected from that world. This is entirely logical on their part, because for 30 years they’ve gotten rich, rich, rich at the same time as ordinary people haven’t had a single raise. When you’re sitting on the top it’s very clear that all boats don’t need to be lifted and that Americans aren’t all in it together. The elites have done just fine, for over 30 years, while the rest of society went to hell.

So there’s no empathy born of shared experience, of the knowledge that sometimes life sucks and no matter what you do, it’s going to suck, and that that’s the way many people live. And there’s no acknowledgment of a need to make America work for everyone, because for the elites, that’s simply not true: America doesn’t need to work for everyone for things to be good for them.

This then, is how they’ve acted. Plenty of help for themselves, for the people they see as part of their group. And very little help for everyone else. Because the elites aren’t like ordinary people, they don’t believe they have many shared interests with you, and they no longer have any real shared experience.

Expect to eat a lot of cake over the next few years if this attitude doesn’t change. The elites, of course, are wrong. At the end of the day a nation without a solid working and middle class always falls into steep decline.

But, as Adam Smith once said, “there’s a lot of ruin in a nation.”

Nonetheless, as many nations have discovered, that amount isn’t infinite.

This is a republished article from 2009. I think it’s worth putting some of these up occasionally, because most readers won’t have seen the original.

Given all the controversy around inequality, this is a must read book.

Given all the controversy around inequality, this is a must read book.