Some stories are too difficult to tell in the hours, days or weeks after you experience them. Over time, however, they fester; begging to be told; becoming more insistent as the months and years pass. Some even begin to haunt a writer more and more, day by day until the tale must be told. Last night’s nightmare compels me to relate my tale now.

In late November of 2008 my bus from Vietnam to Siem Reap developed issues and required a stopover in the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh. It had been a sleeper bus so we were told we’d have a full day in the capital and the bus would leave the next day. Traveling plans like war plans rarely survive contact with the road. Growing ever more patient with detours, I inspected my guidebook, back when using Lonely Planet’s was a thing, and planned my day.

Let me be clear: I am no fan of war or atrocity porn, but I do understand its allure, although I am, thankfully, largely immune to it. On the other hand and possibly more importantly, I also recognize and empathize with the need to preserve places where truly reprehensible atrocities of human history occurred. They are to be preserved that future generations witness, feel, and have the opportunity to comprehend even the smallest portion of the enormity that took place underfoot. Maybe, just maybe, such lessons might be passed on to others who will never be able, or be allowed, to experience such hallowed ground.

Many practicing and secular Jews make pilgrimages to sites where the Shoah occurred. I’ve inquired why and each query has been answered universally. They describe a compulsion to bear witness, to honor the fallen, that they remain alive in living memory. Hard to argue with. Because the Armenian genocide occurred in a more dispersed manner Armenian pilgrims face much more significant hurdles. But, when possible Armenians likewise honor their ancestors. I cannot speak to what happened in Rwanda in 1994. I am aware of such places in Guatemala, heard in faint whispers where no gringos are welcome, nor visit, quite understandably.

How to explain how my choices that day were made? I may have only been 13 years-old but the 1984 movie ‘the Killing Fields’ left me with a powerful impression. An impression I recalled that November day and I felt oddly, inexplicably, duty-bound to see what I did not want to see. The killing fields were not my first stop that day however. That honor (poor word choice, I know) fell to the former interrogation and torture center of the Pol Pot Regime’s perceived enemies Tuol Sleng. Here I endured, what I can only describe as a feeling of almost unbearable witness to sickening crimes.

Two, and only two, examples need suffice.

First, in one room of the prison sat a metal frame bed where regime “enemies” were restrained. Once restrained, electrical leads were attached to the frame. Most expired for no reason at all. Sometimes the guards just left the room to have a smoke. At others they left to eat lunch. But most often the guards let them die because they knew no questions they might ask would be satisfactorily answered. They knew they were killing regular people, completely innocent.

First, in one room of the prison sat a metal frame bed where regime “enemies” were restrained. Once restrained, electrical leads were attached to the frame. Most expired for no reason at all. Sometimes the guards just left the room to have a smoke. At others they left to eat lunch. But most often the guards let them die because they knew no questions they might ask would be satisfactorily answered. They knew they were killing regular people, completely innocent.

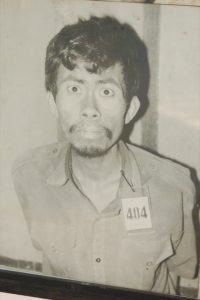

The second example is this photo, a photo that haunts me to this day. The walls of Tuol Sleng are papered with them, all of them innocent and to this day they go unnamed. If you cannot feel the fear radiating from this photo you are devoid of the empathy gene.

In all I spent about two hours wandering through Tuol Sleng. I will never return.

But, my day was far from over. After walking out of Tuol Sleng I hailed a tuk-tuk and asked him to take me to the killing fields, which are about two kilometers outside of Phnom Penh. What I recall most vividly about this horrifying place was the care I had to take where I walked. (NOTE: click on the following links at your own risk.) The ground was uneven and I was told at the entrance to stay on the high ground, as the sunken spaces were mass graves. Christ, I shudder visualizing it even now. Then there were what I can only describe as large glass cases, best suited as terrariums for large pythons or boa constrictors. Each case was filled with one of the following: femurs of the dead, human ulnae and radii, and hip bones. Piling Pelion on top of Ossa, mason jars filled with human teeth sat atop each glass case. Finally, the Cambodians being Buddhists made a four story glass stupa—a Buddhist reliquary—filled with human skulls.

Towards the end of my increasingly heavy-hearted meanderings I noted crimson rays filling the sky. I hailed a cab to my hotel, shambled up to my room, slouched off my backpack and sank onto the bed, sighing deeply from emotional exhaustion. I didn’t know what I felt—except despair. I walked downstairs and asked where the nearest bar was. Now, I am not one to drink alone; but, I confess that I was incapable of dealing with what I was feeling at the time. So, I sat down, alone and in silence and got drunk. Not tipsy, but drunk. I barely recall making it back to my room, but I did. The last thing I recall thinking before I passed out was, “I’m going to be haunted by this for a long time.”

The next morning after dreamless sleep, no ghosts woke me up. All that greeted me were overcast skies, a wicked hangover and my noon bus ticket to Seam Reap.