To understand how tariffs are going to hit various economies, you need to understand how neoliberal era trade and production was set up. In the old world supply chains were much less integrated. In general, if you made it in your country, your supply chain was in your country. There were always some exceptions, especially for resources like nickel, copper, uranium, etc., but these were the exception to the rule. Trade deals and laws in the old era usually required foreign companies which were set up for production in a host country to source a minimum amount of parts from said host country. Almost always this was over 50 percent. If the infrastructure didn’t exist, the company, usually with government help, would set it up.

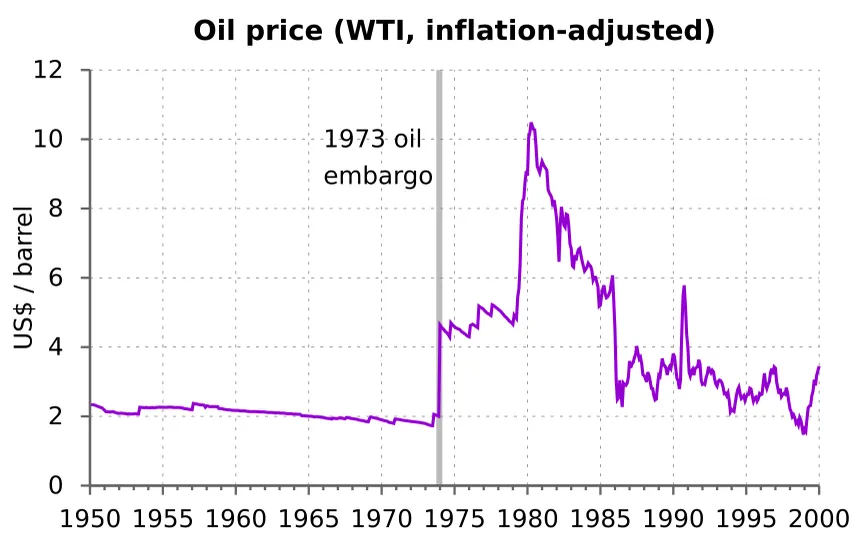

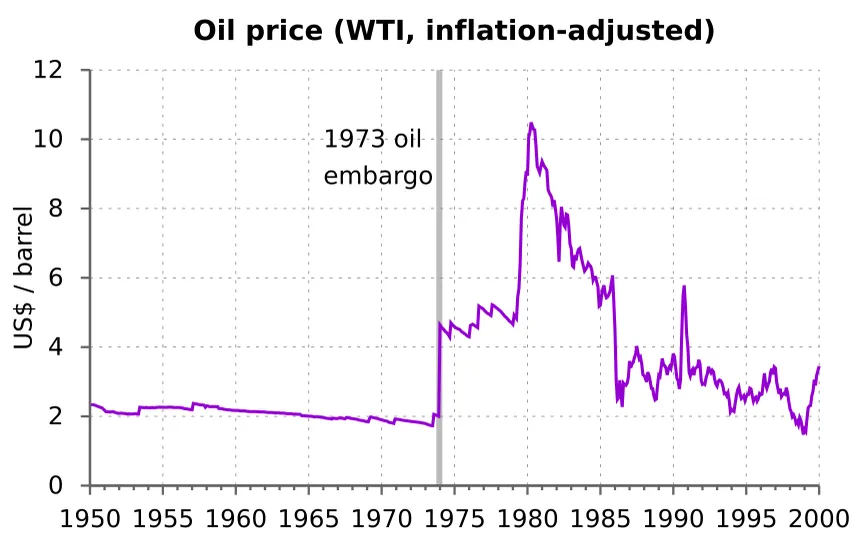

Understand clearly that the neoliberal era came out of the inflation crises of the 70s. It had two goals: 1) To reduce consumer inflation and thus growth in petrochemical use, and; 2) To make the rich much richer.

In the post-war era, most production in most Western countries was meant for the internal market. If you needed it, you made it, with some exceptions: The smaller you were, the more you needed to import some goods, and of course, if you’re Norway or Canada you import bananas and coffee, and you imported any resources you couldn’t produce enough of yourself, like wood, oil, gas, and minerals. The high imports of oil were the old world’s achilles heel, and the inability to import substitutes away from them killed it.

So, most things ordinary people bought have an oil input cost, and the more money ordinary people had, the more they’d do things which had an oil cost. There was almost nothing the Arabs needed to buy from the West at the time: They had small populations, and didn’t have consumer economies. We could sell them military goods, but other than that their needs were modest. They had us over an oil barrel.

I remember the post-war world well, it died in stages. In the 70s and 80s, my family lived in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Bangladesh at various times. In all these countries, even Singapore, everything was cheaper than in Canada or America. Ex-pats who had incomes denominated in first world currencies lived very well. When in Canada, we were lower middle class. Overseas we had servants.

Yet despite having cheap goods and services, all those countries except Singapore were third world. Poor.

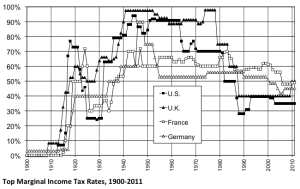

The post-war developed country play was to keep both prices and wages high, and to make sure wages went up faster than prices, while controlling asset prices, which included home prices and rent. Wages were high because prices were high, and because most production was done in country, or in another high wage country, and because there were tariffs on goods from low cost domiciles, and as they didn’t have much industry anyway, it didn’t matter. Even as late as 1980 or so, America made 97 percent of everything it needed, and the Japanese export surge which changed that still came from a first world, high wage/high cost nation.

In this world, there was certainly trade, but countries still strove to make and grow as much of what they needed as they could at home.

Then came the inflation crises, when due to the oil shocks, wages grew slower than prices — a lot slower. I remember the price of a chocolate bar going from 25c to a dollar in the period of two years (I was a kid, so that’s the sort of price that was important to me. Paperback prices also went from about 99c to $2.50 and then up to $3.50).

So, if you’re going to tackle this, you need to reduce the use of oil, which means reduce ordinary people’s use of oil, which means restraining their income growth. This is why, during the 80s and 90s, every time wages grew faster than inflation, the Fed would slam on the brakes and cause a recession.

But the other play, which also helps keep domestic wages down, is to manufacture and grow and produce in really low wage domiciles. You can slowly crush European, American, and Canadian wages, but people in China, Bangladesh, Mexico, India, and so on are already earning one-tenth of what you have to pay first world workers. They were a lot less efficient workers, too, but even so, if you offshored production, you could reduce the price of goods.

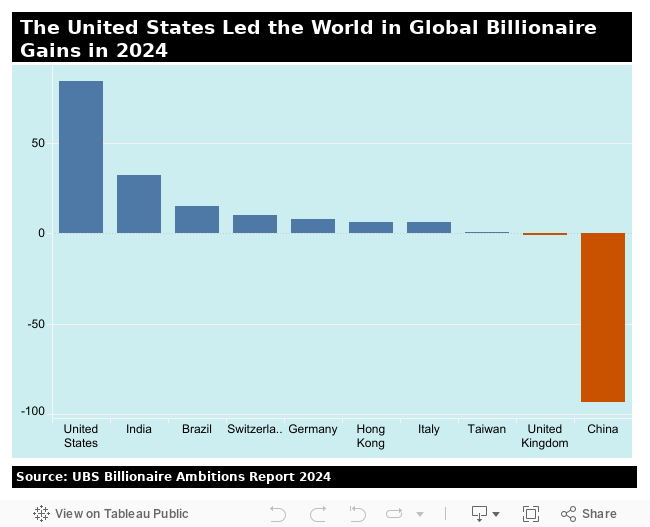

So offshoring became a way to reduce inflation. It also juiced profits, since much of the price decreases weren’t passed on to first world consumers, but hey, win/win if you’re a first-world capitalist or financier. Because production was being increasingly farmed out to developing nations, first world economies financialized and the financial elites took control from the old manufacturing elites (who were, for all their flaws, actually capitalists. Financiers are the lowest form of capitalist life.)

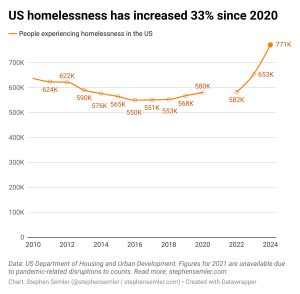

This, of course, lead to first-world countries de-industrializing, and eventually to the rise of China, and the loss of the West’s tech lead, along with the evisceration of the middle class, a huge homelessness crisis, and in Europe, sclerosis.

Now here’s the irony: China has very low costs, so low that I’d argue that the idea that they’re still middle income is false. Their ostensible salaries look low to us, but cars in China can be had for 10K. Earbud equivalents can be had for less than $10. Smart phones are cheaper. Almost everything is cheaper. It’s a weird inverse of the old first world situation: Wages are lower, but costs are lower vs. wages are higher, and so are costs.

Either equilibrium, of course, works for prosperity. What the first-world now has is high-ish wages and higher costs. I saw a factoid the other day that claimed that rent has increased 350 percent more than median wages in the US since 1985, for example.

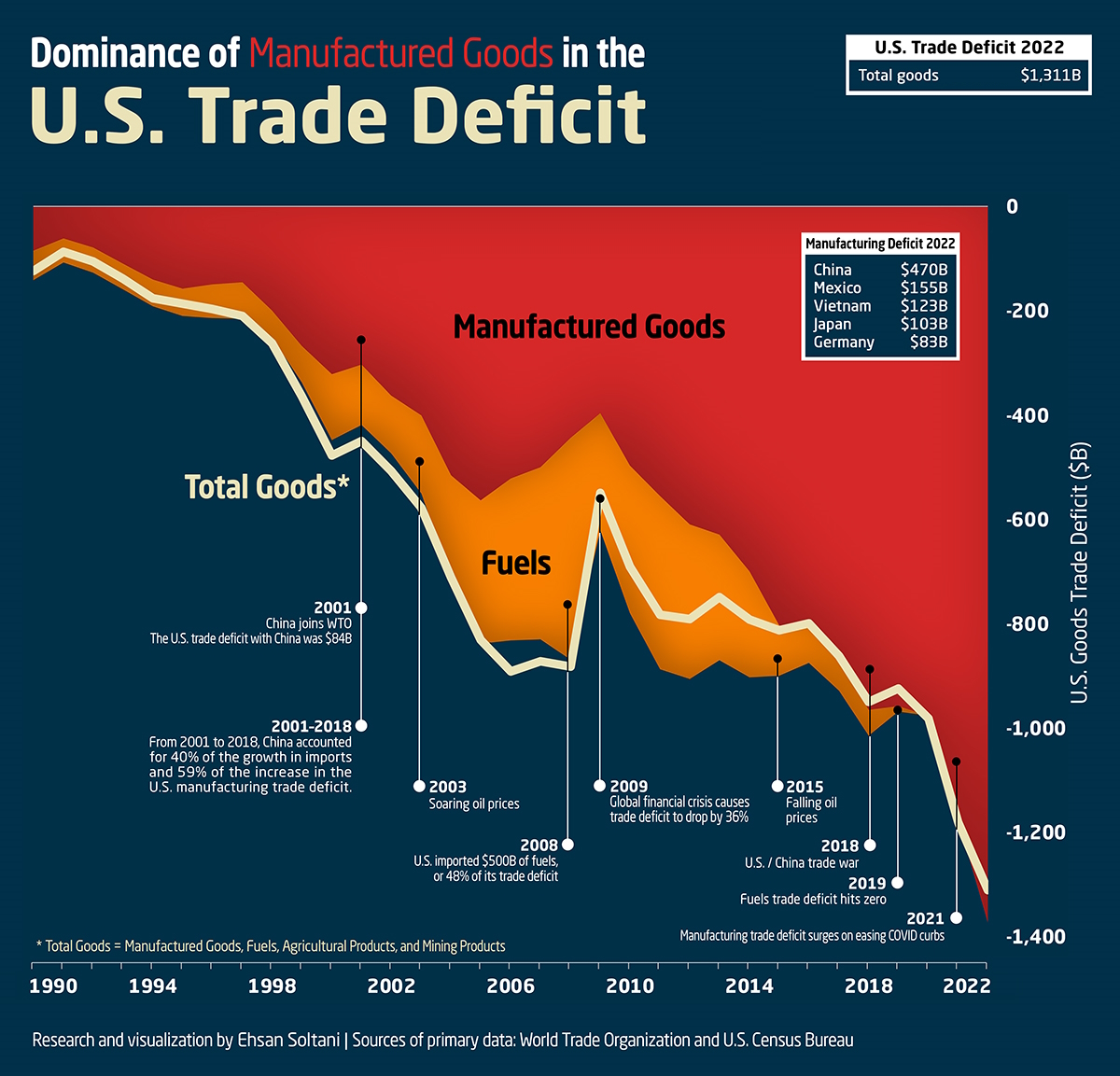

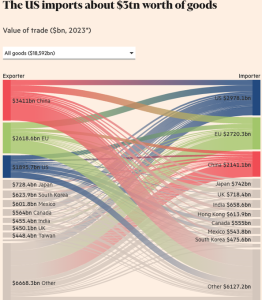

Now, let’s take closer look at the structure of trade in the neoliberal era: It was based around trade agreements like NAFTA and the WTO which made it essentially illegal to run old-style economies where most production for internal markets was domestic. You couldn’t tariff, you couldn’t subsidize, and you couldn’t enforce ownership rules, domestic content rules, or even rules requiring primary processing of raw resources before export (for example, Canada didn’t used to ship raw logs and canned salmon before selling it overseas.) If you did, the independent trade courts would hit you with huge multi-billion dollar fines. You also had to enforce American IP laws, and thus pay a portion of most profits to America.

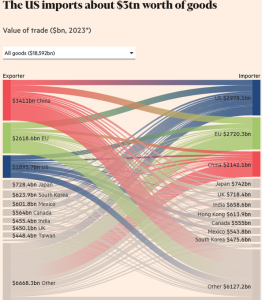

What this lead to is countries becoming cogs in production networks; they had part of the supply chain for a product without having most of the supply chain. Their economies were dependent on trade because even if they assembled the final product, most of the supply chain was outside their country.

Let’s take an example from Canada’s current dilemma with regard to American tariffs. Canada’s government made some big bets on EVs, especially batteries. It seemed to make sense: We produce the minerals which go into batteries, so why not manufacture them here and ship them to the US?

This was a BIG bet in Canadian terms. Ontario and the Feds put up about 16 billion of subsidies, perks, and land to get VW to build a battery plant in St. Thomas. This plant, if it goes into full production will produce a million batteries a year. Stellantis’s battery plant in Windsor had 15 billion dollars in subsidies. Honda is retooling to make EVs in Canada, and to produce batteries, and other parts, for EVs — with a 2.5 billion tax cut deal and 2.5 billion in direct and indirect subsidies.

Now here’s the issue, which you may have spotted: They’ll make way more batteries than Canada could possibly need for domestic EVs. Way, way more. With tariffs and uncertainty (after all Trump, could increase them again) none of these projects are viable. Perhaps we could re-tool one of them and really push Canadians to switch en-mass to EVs. If the Feds are smart, that’s probably what they’ll do. (Spoiler, the Feds are not always smart.)

But no matter what, Canada’s taking a huge hit.

In the old world, where you produced primarily for yourself, and if it was more expensive than foreign alternatives said “eat tariffs”, and maybe subsidized, a foreign government couldn’t just decide one day to destroy your industry. Trade was usually in products the other nation didn’t make or grow itself, or genuinely couldn’t make or grow enough of.

The neoliberal trade structure was designed to make national autonomy, in anything (food, energy, manufactured goods) extremely difficult to obtain. It was a giant hostage situation.

It broke down because of stupidity and greed. The full story is long, but the essence is simple: Americans gave China the full stack. The entire supply line for a lot of goods is domestic for China with smaller chunks in close by allies like Vietnam. They were low cost, they had real competitive markets which kept prices low, and, because the manufacturing floor was in China, they eventually took the tech lead. This required about 20 years.

So China’s now the only nation in the world that has an old style “post-war” economy: It now produces primarily for the domestic market, but it also gets the neoliberal era advantage of selling huge amounts of goods overseas. Win/Win. For them.

What Trump’s team (not so much Trump as certain advisors) is trying to do is to re-shore a full manufacturing stack to America. They noticed that everyone industrializes behind some form of price supports, and that usually those are tariffs (China used currency controls), so they’re instituting tariffs. Given that the market for a lot of goods is in the US, they figure, correctly, that a lot of manufacturing will be forced to move back to America.

All those batteries Canada is making.

This screws every single American ally who allowed their economies to be restructured by American lead trade deals in the 80s and 90s. Every single one.

That’s why Canada and Mexico are in for a world of hurt, and also the EU. It’s also why China is not in for a world of hurt — they’ve got the full stack, and a massive domestic market. Plus, because their goods are cheap, they’ve got almost the entire global South plus most of the SE Asian economies as customers.

And here’s the problem for America: All its got is the US market, because it’s fucking every major trade partner it has. The allies (ex allies?) have to go back to an old style economy too, or form a much smaller and stupider neoliberal bloc, and if they can’t sell to America, they aren’t going to buy from America either. So America can get some full stack back, but only what it’s economy can afford.

And the American economy is much smaller than it looks. Much, much smaller. GDP numbers are massively over-inflated by asset price bubbles, much of the income from foreign assets is going to dry up, almost certainly eventually including IP. If you can’t sell to the Americans, why enforce their IP laws and pay them? Foreign ownership rules will start popping back up, and US assets overseas will be sold to locals — often at cents on the dollar. Of course, the same will happen to foreign assets in the US, but the “world” the US inhabits economically will shrink.

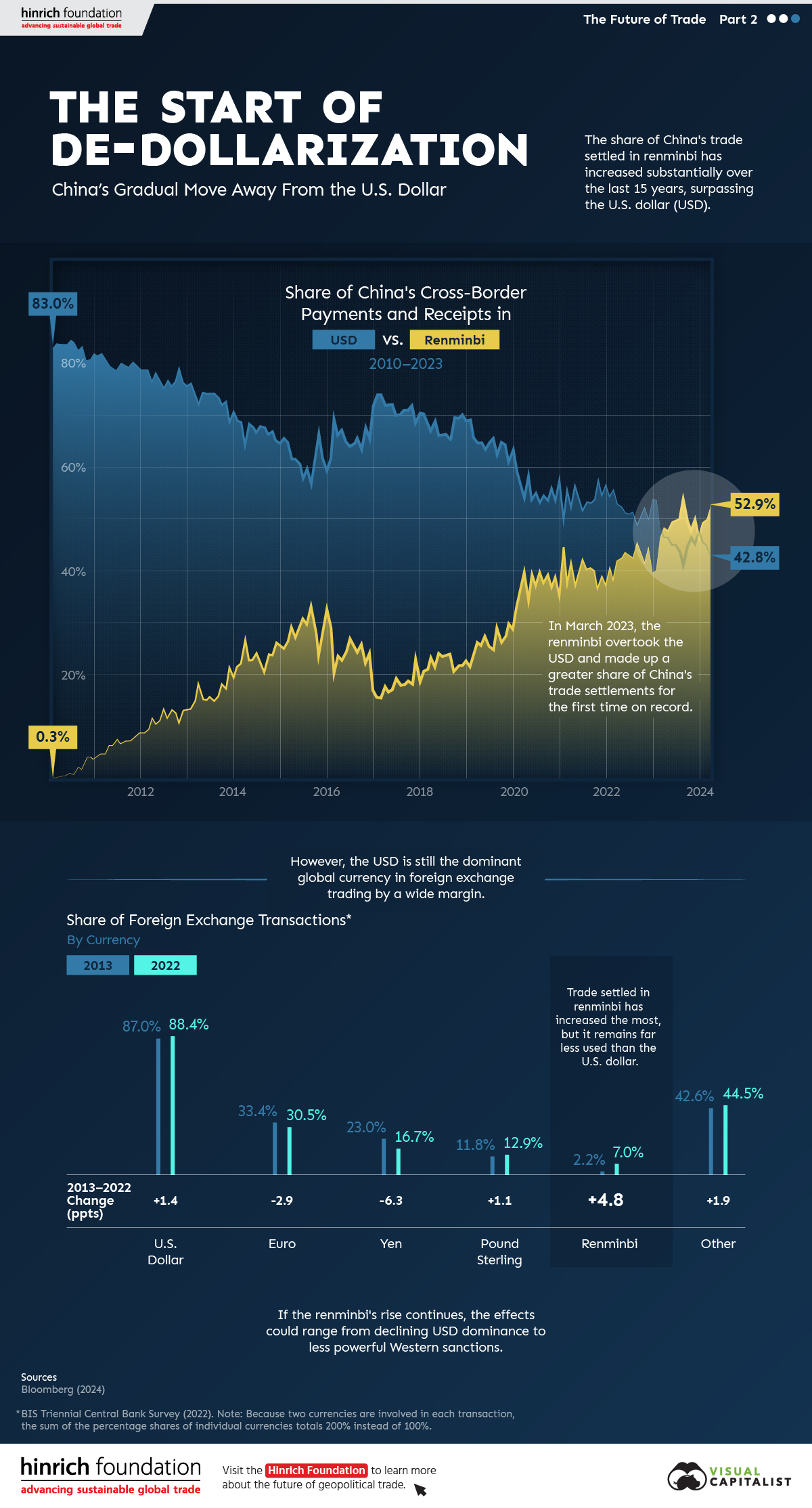

And then, if you can’t sell to the US, why the fuck are you using the US dollar for trade? Trump has made huge threats of tariffs against anyone who moves off the dollar for trade, but if you already effectively can’t sell to the US, again, who gives a fuck? Tariff away, asshole.

And when dollar’s hegemony disappears, the US economy will deflate to its actual size — at least a third, and probably half as large as the official numbers. Think someone pricking a water balloon. It’s going to be amazing to watch.

And that, children, is the end of the American era and Empire. It is very close now, and Trump is making it happen much faster. All praise Trump.

(There’s a lot more to unpack about the effects of Trump’s trade wars but this article is already over 2,000 words. For example, will Trump successfully reindustrialize America and make America, if not great again, at least a decent place to live? More on that soonish.)

You get what you pay for. This blog is free to read, but not to produce. If you enjoy the content, donate or subscribe.

The final part of the economy is what you can get from other nations. Call this the external economy. Does someone else make it, will they sell it to you, can you afford it? Most of the time countries won’t sell other countries nukes, for example, and for much of history countries tried not to sell other countries the knowledge required to make advanced techs. When they didn’t prevent this, they paid big time: Britain was de-facto subjugated by America and America is now losing its Empire.

The final part of the economy is what you can get from other nations. Call this the external economy. Does someone else make it, will they sell it to you, can you afford it? Most of the time countries won’t sell other countries nukes, for example, and for much of history countries tried not to sell other countries the knowledge required to make advanced techs. When they didn’t prevent this, they paid big time: Britain was de-facto subjugated by America and America is now losing its Empire.

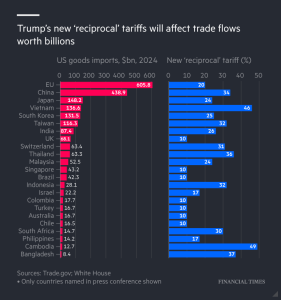

So, Trump’s tariffs are out. He claims they’re half of what each country tariffs the US, but in fact they appear to have been determined by dividing how much the US sells to a country by how much that country sells to the US.

So, Trump’s tariffs are out. He claims they’re half of what each country tariffs the US, but in fact they appear to have been determined by dividing how much the US sells to a country by how much that country sells to the US. The tariffs on each country should have been individually determined based on what America buys from them, and what America sells to them. If it’s something the US can’t make, or given opportunity costs shouldn’t make (do you want to build more power plants for AI, or use it for aluminum?) then those things shouldn’t be tariffed. And if you’re buying what you really need from them, and can’t make yourself or shouldn’t (Canadian potash and aluminum, for example) then why are you tariffing? The Canadian example is a good one: Canada imports more manufactured goods from the US than it exports to America. Tariffs encourage Canada to buy less goods and re-industrialize, reducing demand for American goods and encouraging American de-industrialization.

The tariffs on each country should have been individually determined based on what America buys from them, and what America sells to them. If it’s something the US can’t make, or given opportunity costs shouldn’t make (do you want to build more power plants for AI, or use it for aluminum?) then those things shouldn’t be tariffed. And if you’re buying what you really need from them, and can’t make yourself or shouldn’t (Canadian potash and aluminum, for example) then why are you tariffing? The Canadian example is a good one: Canada imports more manufactured goods from the US than it exports to America. Tariffs encourage Canada to buy less goods and re-industrialize, reducing demand for American goods and encouraging American de-industrialization.