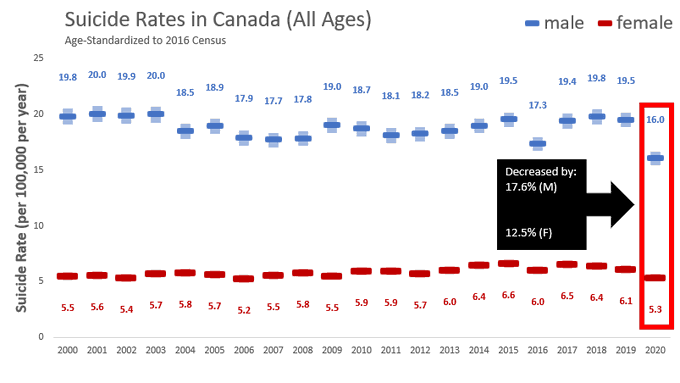

So, there are different measures of creativity. One of them is divergent thinking, the ability to come up with lots of different ideas. George Land created a famous test for NASA, then applied it to children. Test-takers were given a problem and then had to come up with many different ways to tackle it.

Land’s dead now but before he died he gave a Ted talk. Generally loathe them, but this one is interesting.

As for the results of his test…

Yeah. Woops. The reason for this is simple (and I can hear some regular readers eyes rolling, since this is a subject I’ve talked about a lot.) School is about coming up with the “right” answer the “right” way. There aren’t 50 right ways. I have many memories of coming up with the right answer in math, for example, using different methods than the teacher and being downgraded for it.

In math there’s often a “right” answer but in other disciplines, there isn’t one. What caused the French revolution or World War I? There isn’t a right answer.

Now, perhaps you’re thinking “but the social sciences and humanities are different.”

Oh, somewhat.

Back in the 90s I used to tutor university students. I’d tell them I could teach them to consistently get a B, but not an A, because the extra step from B to A was knowing the person who is marking your tests and essays, and both working them so they like and respect you and tailoring your answers to their prejudices. It’s actually harder to get get an A in the humanities and social sciences than in the sciences and in math. I’ve gotten 100% on a chemistry or physics test. I have never done so on a paper or non multiple choice test in the humanities or social sciences because there isn’t a correct answer.

But you will get higher grades if you learn to give the marker about what they want.

In the sciences it’s about getting the right answer the right way. In the humanities and social sciences it’s a social game of “please the market” or in very rigid standardized tests of “please the test designer.”

In realm of the real world this leads to the something called “best practices”, which I loathe. There are no such things as best practices. That doesn’t mean you can’t teach workers what is known to work, but if you enforce “best practices” then they can’t innovate. If you tell people “how” to do something, rather than say “I need you to accomplish X” you shut down learning and creativity and you also strangle advancement.

People have to be free to try new things. There are degrees of this, of course, in some cases the task still needs to get done. But mandating how and not what stiffles progress and creativity faster than almost anything else.

What we do to children and adults is psychologically cripple them. It’s better, in our society, to be wrong with the pack or in the approved fashion than to be right against the pack or using non-standard methods.

Very, very much better. In the pack, wrong with the pack, or more accurately wrong in the way leader-teacher wants you to be, you’re safe.

But get it right the wrong way, or get it wrong trying something new, and you’re toast.

We all know this, but many of us refuse to admit it and this is especially true with regards to school. We spent more awake time in school for twelve to sixteen or more years than we did anywhere else, except in some cases home. That creates strong identification. We either want to believe school is good, or we rebel against it, but very few people can remain neutral. If something “must” be then it must be good.

But school teaches (eye-roll time) us to be a bunch of conformists, giving teacher what they want in the way they want, sitting down and not even talking or using the bathroom without permission.

That’s school and denying that is what school is is rank stupidity.

It’s also most workplaces. You replace teacher with boss.

And then you think you’re free when you’ve spent most of your life doing what you were told, the way you were told to do it.

(By the way, one corollary of Land’s test is that you started out as a creative genius. Perhaps you can be one again? It’s not nature that made you un-creative. Nature started you as a genius.)

The results of the work I do, like this article, are free, but food isn’t, so if you value my work, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.