Question:

If you could not buy anything you wanted using Western currency, why would you sell anything to the West?

Western sanctions on Russia are fairly close to: “You can sell us oil, wheat, and gas, but we’ve frozen all your foreign currency reserves we can touch (almost all of them), and we won’t sell you anything that’s useful to you. Anyone who tries to do so using our system is committing a crime, even if not in one of our countries, and we will punish them.”

It’s hard to imagine that Russia is going to keep selling us what they have. Naked Capitalism reprinted a good article by Olga Samofalova (second half, you can skip the first.):

Stopping gas supplies to Europe is even more disastrous in terms of consequences for both sides. Russia will not be able to transfer West Siberian gas, which goes through European pipelines, to other markets. There is no gas pipeline for such a volume to China or other Asian countries. To send gas by sea by tankers, it needs to be liquefied, but Russia does not have so many LNG plants for this, or gas carriers too. This means that Russia will have to stop production. ‘In the western direction, if without Turkey, there is about 150 billion cubic meters of gas from Russia. Where will we put so much gas if we don’t supply it to Europe? Nowhere. We’ll have to stop lifting the gas. This means that the world market will lose these volumes, and immediately there will be a large deficit of gas in the supply-demand balance of the European Union,’ says Yushkov.

‘No matter what anyone says, Europe will have nowhere to take such volumes of gas from. The world is not able to increase production by 150 billion cubic meters. Europeans will try to switch to other energy sources. An attempt to switch to coal will fail, since Russia is also the largest supplier of coal to the EU. The Europeans will try to launch everything that is possible: all the shut-down nuclear power plants [to reopen], the closed coal deposits in Germany and Poland.’

Now, this isn’t quite accurate. One of the main reasons that Iran is finally getting a renewal of the Iran deal is that the West needs oil and gas supplies from Iran back on the market. But even so, there will be a huge effect.

The core thing to understand here is that we in the West don’t know how to handle supply shocks. The last generation that knew how was the Lost, and they’re all dead. No one alive even remembers a properly-handled supply side shock, as we mishandled the OPEC oil shock catastrophically, and even those people are mostly aged out, unless they’re 80 and in Congress.

The Covid supply shocks have pretty much proved it. We could go into all the issues like price gouging, monopoly concentration, supply chain dispersal, just-in-time, consolidated shipping, the hollowing out of the trucking industry, and blah blah, blah, but it doesn’t really matter. Bottom line, we aren’t handling it well. All we really know how to do is raise interest rates and use central bank policy to keep wages below the rate of inflation, thus making the majority of the population even poorer.

So what happens when Russia cuts us off from a whole pile of minerals, hydrocarbons, and food that we need? Russia is the number one wheat exporter. Ukraine is #5. Gas we’ve already discussed. Oil will spike. Energy costs will go through the roof. Most titanium comes from Russia and is used to build planes, and if Boeing and Airbus have cut Russia off even from repair manuals and spare parts, why should they let the West have any?

I’m not 100 percent on this, but if Russia reacts the way I believe it would be rational for them to act, then we will have a supply shock bigger than the OPEC crisis, especially as it is being added to the Covid shock. Our companies will, of course, use the opportunity to increase their profits even more and price gouge (something they mostly didn’t do in the 70s), and we will get massive inflation.

I lived through the 70s. In the late 70s, during a period of about two years, the price of candy bars (you can tell how old I was) went from 25 cents to a dollar.

This is likely to be worse.

The Russians are also just not going to pay back their debts to Western countries in any form they can use. A law has already been passed where companies owing money to countries with sanctions can pay in rubles to the Russian government, who will then handle any negotiations, for example. More such measures will continue. Freezing reserves amounts to theft, and Russia is not going to pay back thieves.

Russia will probably also break all Western IP. With some under-the-table Chinese help, they’ll then set up production.

Meanwhile, China is thrilled — whatever they’re saying. Xi recently told the Central Committee that China could not rely on world markets for food security. But as a locked-in junior partner with a land border, Russia is a safe provider, especially since a lot of markets will be closed to it, and as we mentioned, Russia’s the #1 producer of wheat. Oil and gas supplies can always be interdicted at the Straits of Hormuz by the American navy, but Russian land supplies are not so simple, etc, etc.

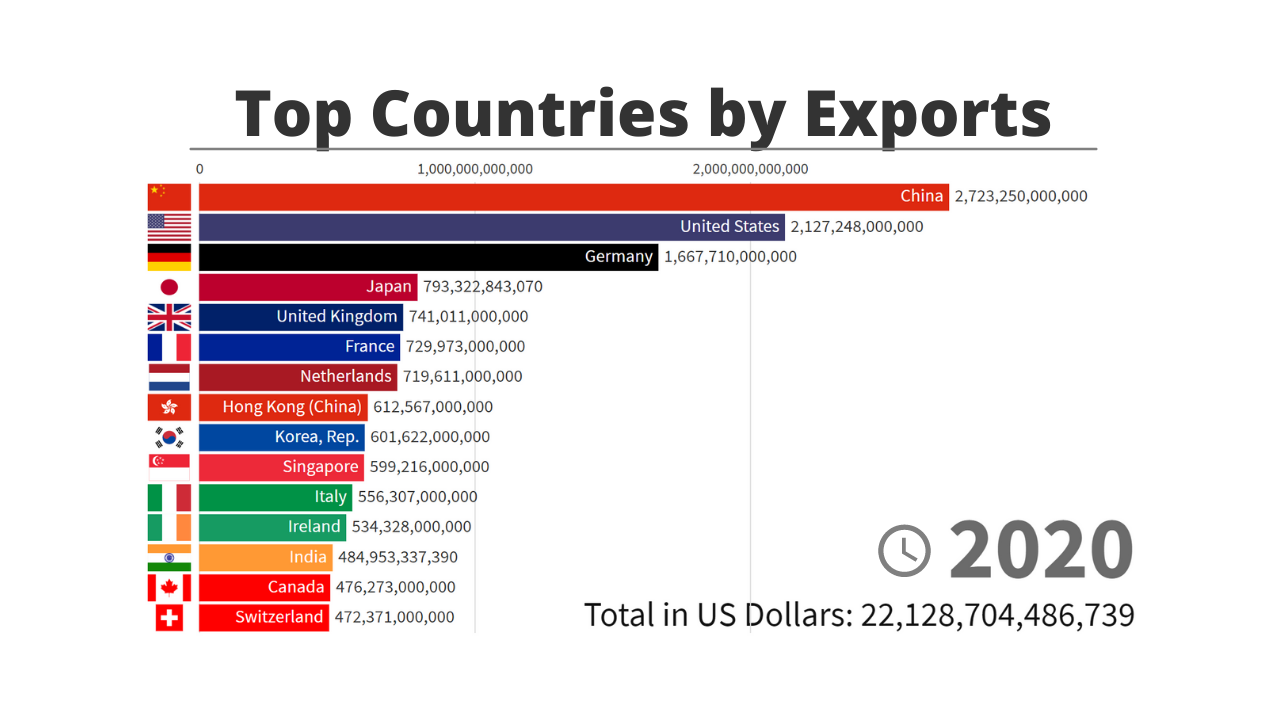

Now, let’s talk about the confusion of money for real economic goods. Money does a lot of things, but money cannot buy what a society cannot produce. Conversely, as Keynes pointed out desperately (and was ignored) anything a country can actually make, it can afford. So when you see things about money, or even stock markets, remember, China is the largest industrial state. Russia is the largest wheat exporter and a vast exporter of oil, gas, and minerals. Russia can survive this if they stop their economy from seizing up, because bottom line, they can feed and heat themselves. The food may be a bit boring, but it’s food.

China is hooking up Mastercard and Visa clients who were cut off with UnionPay and their Mir Card. This isn’t something that would happen if the CCP didn’t give the green light, not a chance. Russia’s SWIFT alternative and China’s are going to be hooked together. China’s banking system actually produces more loans than the US at this time, so they’ll keep the Russians afloat.

Many people think the Chinese will screw the Russians since the Russians need them so badly. They may, but I don’t think so. This is Western thinking, the same stupid, short-sighted greed that led us to ship the majority of our industrial base elsewhere, so a few oligarchs and politicians and consultants could get rich.

China needs an ally. They need good will. Give Russia cheap loans and help when they need it, be the country that helped them when almost no one else would or even could, and Russians will remember that for generations. China doesn’t need a resentful ally, they need a willing, happy, and healthy one. They don’t need an ally who they’re strangling with debt, and right now, loading Russia down with usurious debt in the middle of this crisis would make things worse.

Remember, people often fail to pay back debts they hate.

Contrary to Western propaganda, while there have been cases where China has loaned countries too much at too high rates, generally, Chinese development loans have been below market rates. This is because what the Chinese want isn’t a revenue stream, it’s resources. So they’ll build your mines, your factories, and your transportation networks, and throw in some smart cities, hospitals, and schools too, as a form of domestic subsidy. What they’re going abroad for is resources.

So my guess is that China doesn’t screw Russia to the wall, helping cripple them further and making Russia resent them during their moment of need. They aren’t modern Westerners. That doesn’t mean they don’t expect things in return, they sure do, but what Russia needs and wants to sell them, lines up perfectly with their needs, and there’s no need to screw Russia. In fact, I expect Chinese technicians to flood Russia and help with their infrastructure issues, oil industry, and so on. It’s enlightened self-interest and enlightened beneficience. To use econospeak, this is a positive sum game.

China and Russia have issues, sure, but they need each other massively, and each of them almost perfectly fixes the other countries weaknesses and needs. Russia will definitely be the junior member of the Alliance (and Russian tendencies to think in realpolitik geopol terms mean they get this and won’t even even resent it, as long as they feel fairly treated.)

The wildcard here is India. India and Russia have had good relations, indeed, have been friends, since independence. The Indian people themselves have genuinely fond feelings for Russia that they don’t have for the West or the US. But Indians hate the Chinese because of their territorial disputes.

If I were China, I’d just go to Modi and settle the territorial disputes generously. Give them a bunch of land, lay it on thick. I don’t expect them to do this, because it’s an emotive issue, but most of the land the countries dispute is basically worthless. It just doesn’t matter if India has that land. If China were to do this, it could probably move India into its alliance group, or at least keep it neutral.

So, let’s assume that Russia survives sanctions. Western elites don’t think it will, but Western elites are used to sanctioning powers like Iran and Venezuela, not a great power that China needs in its pocket, which has a huge land border with China. It’ll be ugly.

Assume Russia retaliates and there’s a big inflation shock. The West tries to get China to enforce sanctions, China says all sorts of mealy-mouthed stuff, but basically doesn’t do anything. The West then has three options:

- Full scale sanctions on China. If they do this, the OPEC crisis will look like a walk in the park. It will be a great depression. China is the world manufacturing center and the West cannot, yet, decouple.

- Targeted sanctions, like the chips sanctions that damaged Huawei so badly. These won’t make China change its mind, but it’s what Westerners do, especially Americans, so I assume this is the default.

- Try and cut a deal.. “All sanctions off and some stuff you want if you cooperate.” This is probably the best option for the West, but I don’t think China will go for it, because ever since Obama, the US has said that China is actually enemy #1. They’ll probably figure (I would) that once Russia is taken out, all deals are off and China is next in the crosshairs.

So what happens is probably #2 (targeted sanctions), at first. The West hurriedly moves some production back home (but not much, rentier societies are too high-cost for manufacturing) and a ton to low cost western allies, like Mexico. Once it feels confident, it ratchets up the sanctions, and we are in full cold war. I’d guess four to eight years, but it’s really hard to time these things. You can know something is inevitable, like this cold war, and not be sure when. I’ve been talking about this for years, and now it’s started. The Cold War is on: It’s just only with Russia right now. It will spread to China. If the West gets too emotional and foolish and tries to force China right now, it could happen with a year.

So we move into a new Cold War, in the middle of terrible inflation and possibly even a depression. One can expect most of the South to go with China/Russia. They may have voted against Russia in the UN General Assembly, but their arms appear to have been twisted hard. As soon as its credible to move to the monetary area China and Russia are setting up, they’re going to move their monetary reserves en-masse — unless they’re a Western client state, because the West has now repeatedly stolen other countries reserves.

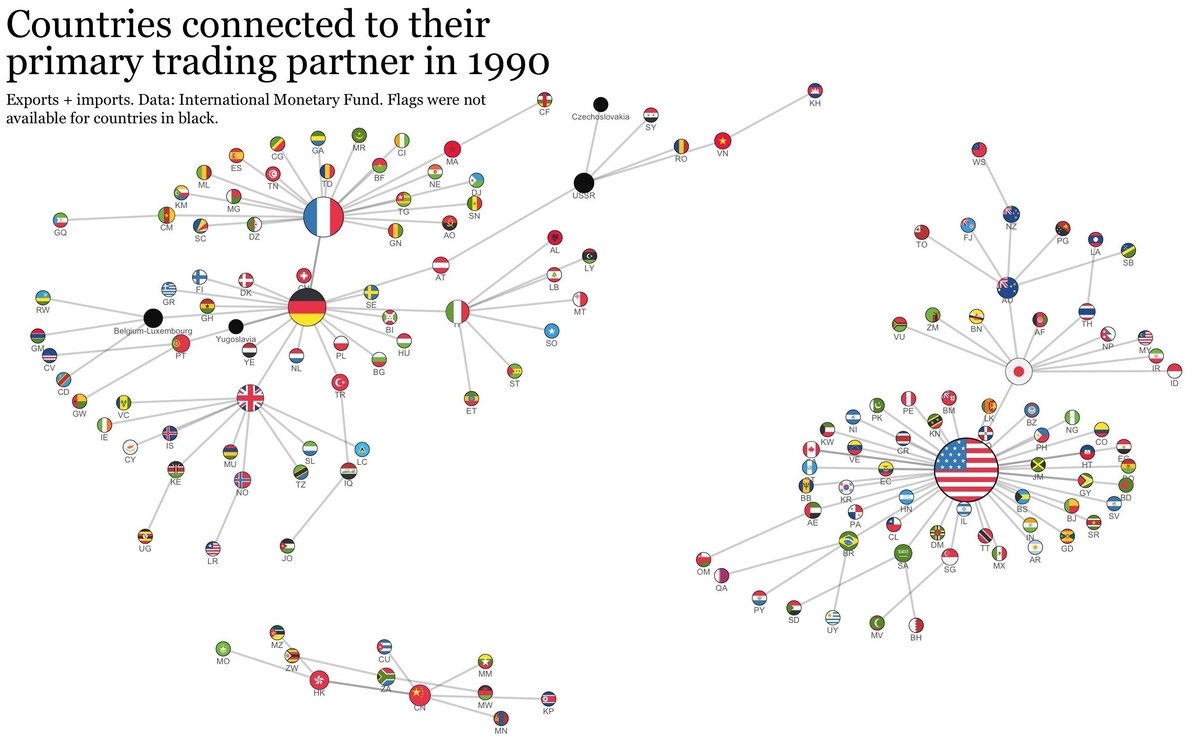

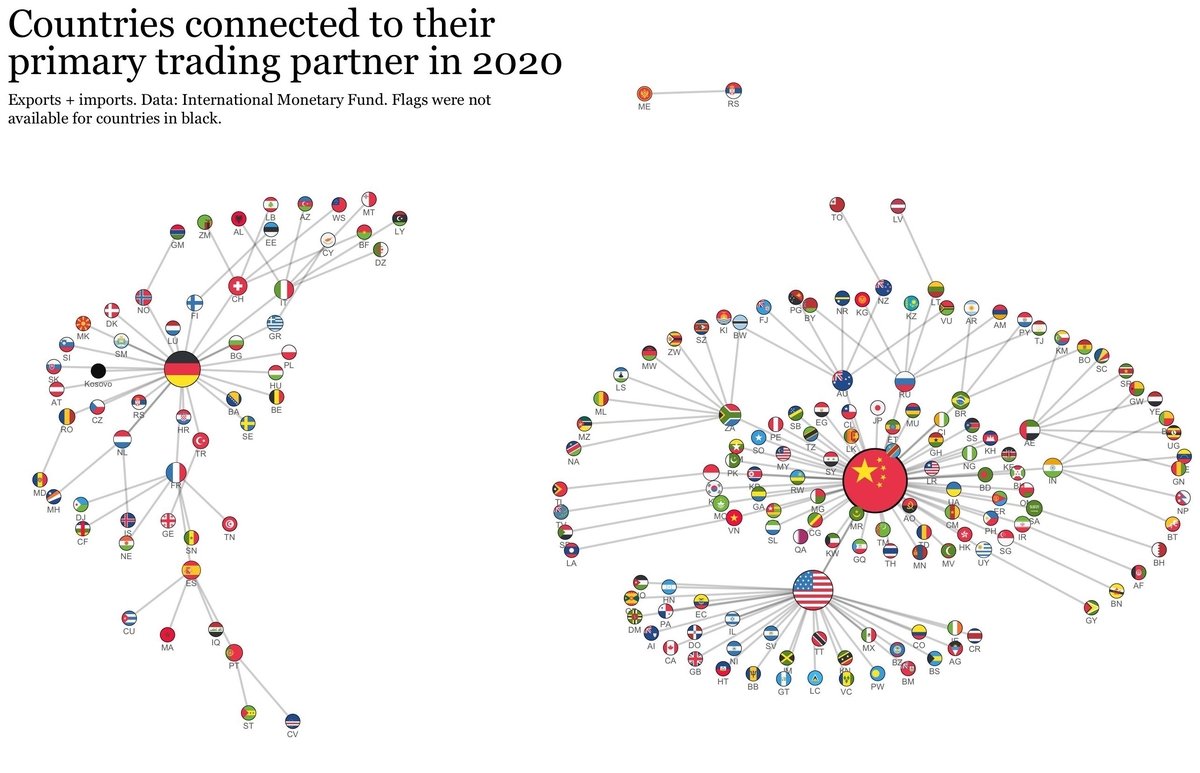

This means most of Africa. Most of South America will want to, as China is their primary source of development loans, but they may be too scared. Any Asian country which isn’t an American ally will go. India is an unknown.

But at the end, you have China which is world’s most populous country, with the biggest industrial base, and even (in purchasing power parity terms) the highest GDP on the other side, along with Russia, and the Number 2 nuclear power, likely still with a massive military, and a ton of southern resource states, all oriented around China. (Though some, like the oilarchies, will try to remain neutral.)

I don’t see this as a competition in which we are the top-dog. Feels like a 60/40 thing to me, and we’re the 40. For too long, we have thought that money and financial games were the same thing as an economy, and that we could just buy whatever we wanted so it didn’t matter who made it, grew it, or dug it up. That world is ending. It was killed by us, with our sanctions, ironically.

Welcome to interesting and shitty times. Put aside your belief in our superiority: We’ve been top dogs for about 200 years now, in some places 500 years, so it’s hard. But all periods in which one group is dominant end, and we’re probably living through that end.

DONATE OR SUBSCRIBE

I don’t want to spend a lot of time on this, but the fundamentals are worth a quick review.

I don’t want to spend a lot of time on this, but the fundamentals are worth a quick review.