This is the second collation of articles on why our world is what it is, and how we can change it. Some of these articles are old, as I don’t write as much as I used to about economics, mostly because the decision points for avoiding a completely lousy economy are now in the past. The last decision points were passed by when Barack Obama announced his economics team and refused to try and get rid of, or bypass, Bernanke to enforce decent policy on the Federal Reserve.

However, this economy was decades in the making, and if we do not understand how it happened we will only wind up in a good economy through accident, and, having obtained a good economy, will not be able to keep it. These articles aren’t exhaustive; a better list would include almost five centuries of economic history, at least in summary, and certainly deal with the 19th century and early 20th centuries.

I was heartened that hundreds of people read the articles linked in my compendium on ideology and character so I dare hope that you will, again, read these pieces. If you do, you will walk away vastly better informed than almost anyone you know, including most formal economists, about why the economy is as it is.

The Decline and Fall of Post-war Liberalism

Pundits today natter on and on about income inequality, but the fundamental cause of income inequality is almost always determined by how society distributes power. As power goes, so goes income–and wealth. The last period of broad-based equality was the “Liberal Period,” which started with the Great Depression. You can locate the end of that era at various points from 1968 to 1980, but 1980 was the point at which turning back became vastly difficult. This was the moment when a new political order was born; an order conceived to crush those who were willing and able to fight effectively for their share of income and money.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing and want more of it, please consider donating.)

Why Elites Have Pushed “Free Trade”

Those who are middle-aged or beyond remember the relentless march of free trade agreements, the creation of the WTO, and the endless drumbeat of propaganda about how FREE trade was wonderful, inevitable, and going to make us all rich. It didn’t, and it was never intended to. Fully understanding why “free trade” has only enriched a few requires understanding the circumstances required for free trade to work, the incentives for free trade, and the power dynamics which make free trade perfect for elites who want to become rich (often by destroying the prosperity of their own countries). Free trade is about power, and power is about who gets how much.

The Isolation of Elites and the Madness of the Crowd

All societies change and face new challenges. What matters is how they deal with new circumstances. The US, in specific, and most of the developed world, in general, is in decline because of simple broken feedback loops. Put simply, ordinary people live in a world of propaganda and lies, while the rich and the powerful live in a bubble, isolated from the consequences their decisions have on the majority of the population, or on the future.

The Bailouts Caused the Lousy “Recovery”

This may be the hardest thing to explain to anyone with a connection to power or money: The bailouts are WHY the world has a lousy economy, not why it isn’t even worse. If people cannot understand why this is so, if they cannot understand that other options were, and are, available, other than making the people who destroyed the world economy even richer and more powerful, we will never see a good economy, ever again.

(I am fundraising to determine how much I’ll write this year. If you value my writing and want more of it, please consider donating.)

The Rapid Destruction of Countries

You may have noticed, you probably have noticed, that most countries are becoming basketcases faster and faster. Some are destroyed by war and revolution, others by forced austerity. However it happens, the end of anything resembling a good economy through austerity in places like Greece, the Ukraine, Italy, or Ireland, or through war, in places like Lybia and Syria, is sure. Understand this: What is done to those countries, is being done to yours if you live in the developed world, just at a slower pace–and one day, you, too, will be more valuable dead than alive.

Why Countries Can’t Resist Austerity

Many of you will realize that much of the answer to this is related to the article on free trade. Weakness, national weakness, is built into the world economic system, and done so deliberately. The austerity of the past six years is simply the deliberate impoverishment of ordinary people, for the profit of elites, on steroids. But it is worth examining, in detail, why countries can’t or won’t stop it, and what is required for a country to be able to do so.

Why Public Opinion Doesn’t Matter

We live in the remnants of a mass society, but we aren’t in one any more (though we think we are). In a mass-mobilization society with relatively evenly distributed wealth and income, and something approaching competitive markets, public opinion mattered. If it was not a King, well, it was at least a Duke. Today it matters only at the margins, on decisions where the elites do not have consensus. Understand this, and understand why, or all your efforts to resist will be for nothing.

Money, my friends, is Permission, as Stirling Newberry once explained to me. It is how we determine who gets to do what. He who can create money, rules. This is more subtle than it seems, so read and weep.

It’s Not How Much Money, It’s Who We Give It to and Why

We have almost no significant problems in the world today which we could either not have fixed had we acted soon enough, or that we could not fix or mitigate today, were we to act. We don’t act because we misallocate, on a scale which would put Pyramid-building Pharoahs to shame, our social efforts.

Higher Profits Produce a Worse Society

No one ever told you that, I’m sure. Read and learn.

The USSR fell in large part because of constant and radical misallocation of resources. This misallocation occurred because those running the economy did not receive accurate feedback. Despite the triumphal cries of the West and the managerial class who pretend to be capitalists, a version of this exact problem is at the root of our current decline, and it would serve us well to understand how and why the USSR fell.

Of all the ideological bugaboos of our current age, one of the strongest is the idea that private enterprise is always more efficient and better. It’s not, but that belief is a very profitable to our elites, and understanding how the engine of privatization works is essential to understanding both our current economic collapse and how the fakely-bright economies of the neoliberal era–especially the early neoliberal period of Thatcher and Reagan–were generated.

It is, perhaps, odd to put this article so far down the list, but it’s wonky and important and not very dramatic. Simply enough, what we define as prosperity is not prosperity, which is why we are sick, fat, and unhappy with rates of depression and mental illness and chronic disease which dwarf those of our forbears despite having so much more stuff. Fix everything else, but if we insist on continuing to produce that which makes us sick and unhappy, what we have will not be what we need or want, nor will it be, truly, prosperity worth having.

The Four Principles of Prosperity

Prosperity, at its heart, is an ethical phenomenon, as much as it is anything else. Without the right ethics, the right spirit, it will not last, nor be widespread. If we want a lasting prosperity, which is actually good for us, we will start by reforming our public ethics.

How to Create a Good Internet Economy

The internet is wonderful, but despite all the cries of “Progress, progress!” it has mostly made a few people rich, created a prosperous class of software engineers who often lose their jobs in their 50s, and has simultaneously overseen the decline of the prosperity for most people in the developed world. It has not produced the prosperity we hoped it would. Here’s why and how to fix it.

Concluding Remarks

The above is so far from comprehensive as to make me cry, but it’s a start. I do hope that you will read it and come away with a far better idea of why the economy sucks for most people, and a clearer understanding of the fact that it is intended to suck, why it is intended to suck, and how the old, better economy was lost.

(Author’s Note: This was originally published October 6, 2014. I’m putting it back up top, as I have gained many new readers since then.)

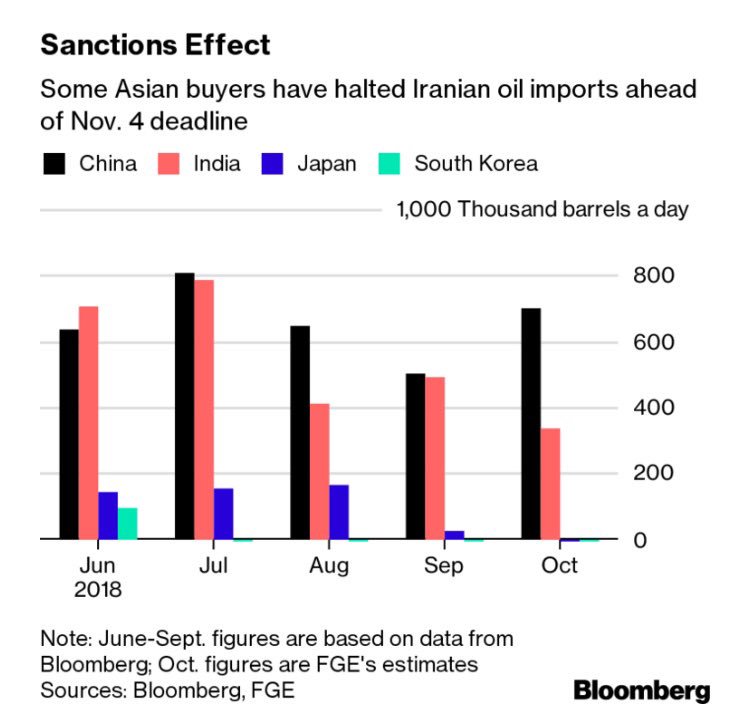

So, the Huawei saga rolls on. The executive arrested, the daughter of the CEO, will probably wind up released, as it’s been made clear this is a political arrest. (Trump has said so, and it’s over Iran sanctions. Breaking Iran sanctions is clearly political, and probably even the ethical thing to do in many cases.)

So, the Huawei saga rolls on. The executive arrested, the daughter of the CEO, will probably wind up released, as it’s been made clear this is a political arrest. (Trump has said so, and it’s over Iran sanctions. Breaking Iran sanctions is clearly political, and probably even the ethical thing to do in many cases.)