A Greek Phalanx

Prosperity is two things:

1) How much you can produce with your technology and social organization;

2) Who gets how much.

The second is determined by a number of factors, but the simplest is the structure of violence. Those who aren’t good at fighting, don’t get as much of the surplus created by society as those who are. Who is good at violence is determined to a remarkable extent by the interaction between the technology of violence, geography and the everyday life of different classes of society.

It has long been noted that in polities where warfare requires a large, organized chunk of the population, more widespread affluence and democracy are more common.

So we have Athenian Greece, where free males fought either as infantry or in the fleets, and where the franchise extended to those who fought. We have Republican Rome, whose legions were originally raised from the citizenry, and which became an Empire when the armies were no longer raised primarily from those close to the city of Rome and when soldiers became more loyal to their generals than to the state. We have the Swiss Cantons, where men fought as close order pikemen and were free, while most of the rest of Europe was ruled by mounted nobles and most ordinary people were serfs. And we have the age of conscript armies in the 19th and 20th centuries, also coincident with a vast increase in democracy and prosperity.

Note that in many of these cases democratic rights extended almost exactly to the fighting class. Women in Switzerland received the vote later than in most of the European subcontinent. Athenian women were infamous for the lack of rights, and the same is true of Republican Rome at its height: the society which defined patriarchy. In Rome there was a separate, higher class, the Eques (Equestrians) based on having enough money to afford to fight on horseback.

All of these places were well known for their prosperity in the heyday of their use of citizen armies. Men too poor to take care of themselves properly (by which we mean eat a nutritious diet) make poor soldiers, and just as poor rowers in a galley navy. There were always rich, and Republican Rome can be understood as partially oligarchical and partially an aristocratic oligarchy depending on what time period you’re looking at, but still, Romans were free, had access to relatively reliable law, and were prosperous.

When they stopped being prosperous as a group, when inequality soared, the Republic went through a series of convulsions (recognized as class wars even at the time), and eventually ended in rule by an Emperor.

The relationship between fighting as infantry, even close order infantry, and prosperity and democracy is not a sure thing. Many of the Greek Polis were not democracies and had frightful inequality, Sparta most famously. Rome fought using close order infantry well into the period of the Emperors, and so on.

Nonetheless, if the method of warfare involves men who must cooperate together and trust each other implicitly, they are much more likely to be free, prosperous, or both. Saxon and Norse England, before the arrival of the Normans is a place where ordinary people have far more rights than the Normans (a Norse offshoot) allow (in part because of Norman forts, meaning that local revolts can rarely succeed, and in which a small number of men can hold off a vastly largely number. It is largely because of forts that Wales, for example, is permanently subdued.) The wealth is also much more evenly spread in pre-Norman England. English history books often start with the Norman conquest, it should be understood that, overall, that conquest was a disaster for the inhabitants of England.

The price of armaments is one of the key factors in prosperity and democracy. If a group of individuals is effective and can win using cheap armaments over those using expensive armaments, again, expect more widespread prosperity and greater rights for the poor. The cutoff point for effective armaments if the cutoff point for widespread prosperity in most cases. If a rifle with a bayonet is all someone needs to be effective, expect the franchise to spread. If it does not spread, expect the first nation to spread it, to be wildly successful on the battlefield: the French revolution is the paradigmatic case.

Of course reactionary regimes can conscript too, but Germans in the late 19th century are more prosperous, even the poor, than those before widespread conscription.

If, on the other hand, effective warfare requires significant wealth, as with Medieval knights, who require a multitude of serfs to support even one fighter, well, expect that those who aren’t good at fighting won’t be prosperous. People today don’t realize how many peasant revolts there were. What is instructive about them is the slaughter involved: the slaughter of serfs and peasants. Often huge rebellions would be put down with only a handful of casualties. Knights were very good at killing peasants armed with makeshift weapons.

If you can kill them and they can’t do anything about it, how much of what they produce is really theirs?

How armaments are made also matters. Even cheap weapons, if they must be made in centralized factories and cannot be made by individuals and small groups, will not be as useful to widespread prosperity as otherwise. The Jeffersonian style yeoman farmer society takes a serious blow in the war of 1812, when it becomes clear that the British centralized manufacture of weapons is more effective than making weapons locally.

The technology of violence interacts with the terrain. Note that in three of these cases we are talking about societies which were born in hilly terrain. Greece, Rome and Switzerland are not flat land. Cavalry is far less effective. Cities have mobs that are effective, even communes, in the Middle Ages, because of how they are laid out. Not only is cavalry useless inside a city, but the narrow streets mean that men can only fight one or two abroad, so even organized infantry has very little advantage in a city. The great broad boulevards of Paris, the wide streets of other cities were created first not for the convenience of the citizens, but so that they could easily be killed in large numbers if they revolted. Medieval cities were free in part because they were very hard to conquer: fortifications, enough money to equip soldiers and streets in which a knight could easily be hauled from his horse and have a knife shoved into the eye-holes of his helmet. And, of course, cities paid a great deal of money for the privilege of being free, often directly either to the king or the equivalent of a Duke; thus putting them under the protection of the most powerful noble in the realm.

Terrain where cavalry can operate freely; where infantry can be bypassed, tends to either be ruled by states or, historically, by nomads, depending on whether it is good for growing crops or for pasture.

Nomads and barbarians, but especially horse nomads, should also be discussed. Much of history can be viewed as a cycle of Agrarian civilizations expanding, being conquered by barbarians or nomads, expanding till they have no surplus due to administrative overload, then being conquered by barbarians or nomads again.

From a population point of view, this is absurd. The Manchu, when the conquered China, probably had 1 to 2% of the population of China. The Mongols were a miniscule fraction of the population of the territories they conquered. But Barbarians have something going for them; every fighting age male who isn’t a thrall or slave is a warrior, and often a very good one. It has long been noted that healthy rural or wilderness people make the best soldiers: Roman recruiters wanted the sons of free farmers. Canadian and Australian soldiers in WWI were far better than English soldiers because they grew up on the farm, well fed as a rule, and shooting a gun.

Unfree or other impoverished rural types are generally not much use in a fight. If they didn’t have proper nutrition as children, they’re worthless. But free rural males are tough, and in a culture where they use weapons, already skilled, generally to a level no “basic training” for conscripts can possibly reach. All basic training teaches such people is how to fight as a disciplined group: the weapon skills are already there.

The Mongols hunted in large, indeed army sized groups, driving the prey before them. They were expert horsemen, master archers using one of the best bows in the world, and they were used to working in organized groups. The Mongols, it is said, hunted like it was war, and made war like it was a hunt.

The specific technology they used was also perfect in an important sense: horse archers choose their battles against slower armies, and can withdraw effectively taking few losses. If the Mongols didn’t want to fight, they didn’t. They only fought, during their heyday, when they had the advantage and as a result they racked up victory after victory.

The everyday structure of Mongol life thus provided most of what they needed to be extraordinarily effective soldiers: it took only uniting them and making some strategic and tactical doctrine changes to turn them into a force that conquered the largest land empire in history, and allowed them to conquer nations which were far, far more populous than they. Note, again, however, the interaction of terrain and technology: the Mongols’ initial conquests were generally in relatively flat lands. (Though not exclusively. Genghis Khan was the last person to really crush the Afghans, after all.)

So we have our trifecta: the Mongols had excellent technology (bows, horses and stirrup); the terrain was suited to their style of warfare; and their way of life made them tough and taught them almost all the skills necessary to be effective soldiers.

BOOM. World Conquest.

Another major factor might be called “not worth conquering”, or (related, but not identical) “area denial”.

This is an important consideration in today’s world. The Coalition attack on Afghanistan was all very fine and good, and they easily conquered the cities, but they couldn’t control the countryside. Guerrilla warfare, to be sure, has been used for millennia (the Romans fought a nasty guerrilla war in Spain.) But modern technology, specifically explosives in the form of mines and their easily made irregular counterpart the IED, make it easy to do area denial. NATO troops in Afghanistan and Iraq had their mobility and their ability to control the country severely curtailed: they couldn’t drive their vehicles down most roads without risk.

The Taliban and the Iraqi freedom fighters thus could not defeat the US army in open field battle, as a rule, but they could bleed them and deny them the fruits of conquest. Much of Afghanistan could not be effectively taxed by the puppet government in Kabul; the same was true in Iraq. In the end, in Iraq, the US military had to pay militias in order to be allowed to withdraw.

This, then, is the question of how effective irregular warfare is. How much loss can under-equipped troops inflict? An American infantryman is expensive; an American tank is more expensive. An American helicopter pilot is precious. An insurgent with an grenade launcher is not. Your expensive troops may inflict higher casualties on the enemy, but they are more expensive and harder to replace.

If the Chinese had been able to reliably inflict one loss on the Mongols per five Chinese losses, they would have won, at least in the early part of the war.

For much of history many areas were simply not worth conquering: the natives were dangerous and had no wealth that anyone else wanted. The fall of the British Empire can be viewed in part as “why are you conquering huge chunks of the world that offer nothing worth the cost of subduing and then administering them?”

The more the locals can resist; the more they can have a good life without creating portable wealth; and the more they are lucky not to be sitting on gold, silver, or oil, the more likely they are to be left to their own affairs. If the wealth of a nation is its people, profiting from its conquest is tricky: if its wealth is a resource that a few people can extract, profiting from conquest is easy.

Being conquered, some exceptions aside, is rarely good for those conquered. India before the Mughals and the British was one of the most prosperous areas in the world. Afterwards it was known for its poverty. India had more manufacturing ability than the British before the British started conquering it, for example. And British India had frequent famines, while independent India does not.

For those involved, this can be a lose/lose proposition: Iraq has been devastated. Afghanistan has been devastated. Some Americans definitely got rich (mostly by stealing from the American government through vast corruption); but both societies lost. Nonetheless, those who will not resist, gain only and exactly what those who win will allow them to have. Republican Romans were not taxed. Their conquests were.

The effectiveness of personal violence also matters. The concealed dagger, the concealed revolver, make assassination possible, even easy. They restrict the mobility of those who oppress. It is not accidental that Nixon, who is President when American inequality is still low and world inequality is declining, goes to see protestors at night with only one aide, and no bodyguards, while Clinton, Bush or Obama would never consider such a thing and Washington DC is disfigured by huge concrete barriers; constant weapon checks and so on.

The more ruling requires the rulers to actually be amongst the ruled, the more the effectiveness of personal weapons matter. Obama can rule behind a cordon of guards; rulers who need to be in contact with the people cannot.

Finally we come to the balance of terror. Weapons that devastate are weapons of terror. Aerial bombardment is about terror, drones with hellfire missiles are about terror. “We can kill you, and we can destroy your infrastructure, and there is nothing you can do to stop us.”

Terror begets terror. Those who are terrorized (and bombing is a terror weapon, let no one tell you otherwise) begets attempts to retaliate.

Terror is remarkably ineffective against non-elite societies until it scales. If you can destroy entire populations, your terror will work. If everyone fears your kidnap and torture squads; it may work. But it doesn’t win actual wars: even World War II strategic bombing was found to be largely ineffective at stopping German production, what it was good at was killing large numbers of civilians.

What terror is good at is dealing with out of touch enemy elites. If you can swoop in, kill the elites, and they cannot stop you, they are more likely to give you what you want without ever having to fight. This is also what conventional military supremacy is good for. Imagine the following scenario: George Bush invades Iraq, publishes a proscription list, and elevates a competent Colonel to be the new leader of Iraq and leaves within 6 months.

That would send a message to elites with ineffective conventional armies all through the world: “we can kill you, personally.”

It does not work against highly motivated ideological organizations. Killing the #2 man in the Taliban more times than I can remember has not stopped the Taliban. Vast waves of assassination throughout large parts of the Muslim world have not stopped the rise of al-Qaeda affiliates or similar organizations. Terror works against people who have something left to lose, or who value their life more than anything else. Against those who are willing to die for their beliefs and who lead an organization or society which agrees with them, it matters little: they will be replaced and their replacement is just as likely to be more competent than less.

But if your elites fear for their lives and do not have strong beliefs they are willing to die for your society will be run, in effect, by the foreign nation which they fear, and while your elites will probably do well enough from bribes, ordinary people will not.

From the point of view of those with an advantage in terror, then, it is best used either as wholesale slaughter, or as very occasional examples. Once people have nothing to lose; or once you have radicalized them, it is almost completely ineffective, and can even be counterproductive, with each new atrocity simply making the masses more determined to resist.

If terror is your weapon, use it sparingly, or make sure your enemies’ ability to resist in destroyed utterly.

Wars of terror are devastating to prosperity. Waves of torture; mass bombing campaigns; serial assassination, destroy either the infrastructure of society or the cohesion and trust required for prosperity. If one side feels it can destroy the other with impunity, you wind up with Gaza.

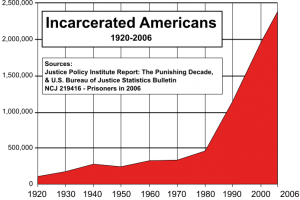

Those who want prosperity must be able to retaliate effectively. If you can be fined millions for “stealing” a few dozen songs; if you can be jailed for, in effect, going bankrupt (the case in America today); if the police can easily defeat the masses; then those who control government and thus control the police can and will take as much of the surplus of society as they want. Those who doubt this proposition are invited to note that the top 10% of society (really the top 3% or so) in America are now taking more than the entire gains of the recovery while America has created a paramilitary police; and an unprecedented in American history surveillance network and has put in prison the largest % of its population in history. These three facts are not unrelated.

Concluding Remarks

There are many in the world today who want to change technology to make the world a better place. If they are concerned with prosperity for the masses let me suggest to them this: cheap weapons that make groups of men and women effective fighters; which require them to trust together and work in groups; are in the long run likely to lead to prosperity. Nor can this empowerment be in area denial alone. IEDs are great at ensuring the writ of the government cannot extend to an area: but they destroy prosperity. Technologies like drones (and effective ground combat robots are about 10 years out), will do the opposite.

By itself technologies that empower organized groups are insufficient. But they are virtually a requirement for widespread prosperity. Without them those who have the advantage in violence will use it to take what they can, and those who cannot resist will live in the conditions their superiors allow.

(Update: reference to droit du seigneur removed.)

The more outside the mainstream you are, the more you will learn it. African Americans, Latinos, poor whites (in that order.) Those who are fundamentally authoritarian, but somewhat opposed to the system (like the Bundy ranch) are treated more carefully (though the militia movement has its martyrs). But the fundamental lesson of life is to do what your lords and masters tell you to, and to not protest any law or order, no matter how nonsensical, trivial, or unjust it is.

The more outside the mainstream you are, the more you will learn it. African Americans, Latinos, poor whites (in that order.) Those who are fundamentally authoritarian, but somewhat opposed to the system (like the Bundy ranch) are treated more carefully (though the militia movement has its martyrs). But the fundamental lesson of life is to do what your lords and masters tell you to, and to not protest any law or order, no matter how nonsensical, trivial, or unjust it is.