In the Anglo-US world, post-war liberalism has been on the defensive since the 1970s. This is normally shown through various wage or wealth graphs, but I’m going to show two graphs of a different nature. The first, to the right, is the number of strikes involving more than 1K workers. Fascinating, eh?

In the Anglo-US world, post-war liberalism has been on the defensive since the 1970s. This is normally shown through various wage or wealth graphs, but I’m going to show two graphs of a different nature. The first, to the right, is the number of strikes involving more than 1K workers. Fascinating, eh?

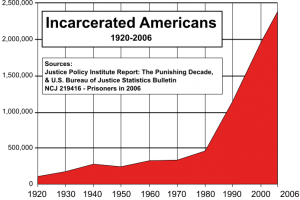

The second, below and to your left, is the incarceration rate. It isn’t adjusted for population increases, but even if it was, the picture wouldn’t change significantly.

This is the change caused by the Reagan revolution in the US, which, as is the case with most revolutions, started before its flagship personality.

I was born in 1968. I remember the 70s, albeit from a child’s perspective. They were very different from today. My overwhelming impression is that people were more relaxed and having a lot more fun. They were also far more open. The omnipresent security personnel, the constant ID checks, and so forth, did not exist. Those came in to force, in Canada, in the early 1990s. As a bike courier in Ottawa, I would regularly walk around government offices to deliver packages. A few, like the Department of National Defense and Foreign Affairs, would make us call up or make us deliver to the mail room, but in most cases I’d just go up to the recipient’s office. Virtually all corporate offices were open, gated only by a receptionist. Even the higher security places were freer. I used to walk through Defense headquarters virtually every day, as they connected two bridges with a heated pedestrian walkway. That walkway closed in the Gulf War and has never, so far as I know, re-opened.

I also walked freely through Parliament Hill, un-escorted, with no ID check to get in.

This may seem like a sideline, but it isn’t. The post-war liberal state was fundamentally different from the one we have today. It was open. The bureaucrats and the politicians and even the important private citizens were not nearly as cut off from ordinary people as they are today. As a bike courier, I interrupted senior meetings of Assistant Deputy Ministers with deliveries. I walked right in. (They were very gracious — in every case.)

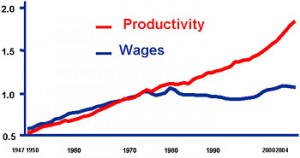

The post-war liberal state involved multiple sectors, in conflict, but in agreement about that conflict. Strikes were allowed, they were expected, and unions were considered to have their part to play. It was understood that workers had a right to fight for their part of the pie. Capitalism, liberal capitalism, meant collective action because only groups of ordinary workers can win their share of productivity increases.

Which leads us to our second chart. The moment you lock up everyone who causes trouble (usually for non-violent, non-compliance with drug laws), the moment you crack down on strikes, ordinary people don’t get their share of productivity increases. It’s really just that simple.

This is all of a piece. The closing off of politicians and bureaucrats from public contact, the soaring CEO and executive salaries which allow them to live without seeing anyone who isn’t part of their class or a servitor, the locking up of people who don’t obey laws that make no sense (and drug laws are almost always stupid laws), the crushing of unions, which are a way to give unfettered feedback to politicians and our corporate masters, are all about allowing them to take the lion’s share of the meat of economic gains and leave the scraps for everyone else.

But why did the liberal state fail? Why did this come about? Let’s highlight three reasons: (1) the rise of the disconnected technocrat; (2) the failure to handle the oil crisis, and; (3) the aging of the liberal generations.

The rise of the disconnected technocrat has been discussed often, generally with respect to the Vietnam war. The “best and the brightest” had all the numbers, managed the war, and lost it. They did so because they mistook the numbers for reality and lost control. The numbers they had were managed up, by the people on the ground. They were fake. The kill counts coming out of Vietnam, for example, were completely fake and inflated. Having never worked on the ground, having not “worked their way up from the mail room,” having not served in the military themselves, disconnected technocrats didn’t realize how badly they were being played. They could not call bullshit. This is a version of the same problem which saw the Soviet Politburo lose control over production in the USSR.

The second, specific failure was the inability to manage the oil shocks and the rise of OPEC. As a child in the 1970s, I saw the price of chocolate bars go from 25c to a dollar in a few years. The same thing happened to comic books. The same thing happened to everything. The post-war liberal state was built on cheap oil and the loss of it cascaded through the economy. This is related to the Vietnam war. As with the Iraq war in the 2000s, there was an opportunity cost to war. Attention was on an essentially meaningless war in SE Asia while the important events were occurring in the Middle East. The cost, the financial cost of the war, should have been spent instead on transitioning the economy to a more efficient one — to a “super-analog” world. All the techs were not in place, but enough were there, so that, with temporizing and research starting in the late 1960s, the transition could have been made.

Instead, the attempt was left too late, at which point the liberal state had lost most of its legitimacy. Carter tried, but was a bad politician and not trusted sufficiently. Nor did he truly believe in, or understand, liberalism, which is why Kennedy ran against him in 1980.

But Kennedy didn’t win and neither did Carter. Reagan did. And what Reagan bet was that new oil resources would come online soon enough to bail him out. He was right. They did and the moment faded. Paul Volcker, as Fed Chairman, appointed by Carter, crushed inflation by crushing wages, but once inflation was crushed and he wanted to give workers their share of the new economy, he was purged and “the Maestro,” Alan Greenspan, was put in charge. Under Greenspan, the Fed treated so-called wage push inflation as the most important form of inflation.

Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chairman can be summed up as follows: Crush wage gains that are faster than inflation and make sure the stock market keeps rising no matter what (the Greenspan Put). Any time the market would falter, Greenspan would be there with cheap money. Any time workers looked like they might get their share of productivity gains, Greenspan would crush the economy. This wasn’t just so the rich could get richer, it was to keep commodity inflation under control, as workers would then spend their wages on activities and items which increased oil consumption.

The third reason for the failure of liberalism was the aging of the liberal generation. Last year, I read Chief Justice Robert Jackson’s brief biography of FDR (which you should read). At the end of the book are brief biographies of main New Deal figures other than Roosevelt. Reading them, I was struck by how many were dying in the 1970s. The great lions who created modern liberalism, who created the New Deal, who understood the moving parts were dead or old. They had not created successors who understood their system, who understood how the economy and the politics of the economy worked, or even who understood how to do rationing properly during a changeover to the new economy.

The hard-core of the liberal coalition, the people who were adults in the Great Depression, who felt in their bones that you had to be fair to the poor, because without the grace of God there go you, were old and dying. The suburban part of the GI generation was willing to betray liberalism to keep suburbia; it was their version of the good life, for which everything else must be sacrificed. And sacrificed it was, and has been, because suburbia, as it is currently constituted, cannot survive high oil prices without draining the rest of society dry.

Reagan offered a way out, a way that didn’t involve obvious sacrifice. He attacked a liberal establishment which had not handled high oil prices, which had lost the Vietnam war, and which had alienated its core southern supporters by giving Blacks rights.

And he delivered, after a fashion. The economy did improve, many people did well, and inflation was brought under control (granted, it would have been if Carter had his second term, but people don’t think like that). The people who already had good jobs were generally okay, especially if they were older. If you were in your 40s or 50s when Reagan took charge in 1980, it was a good bet that you’d be dead before the bill really came due. You would win the death bet.

Liberalism failed because it couldn’t handle the war and crisis of the late 60s and 70s. The people who could have helped were dead or too old. They had not properly trained successors; those successors were paying attention to the wrong problem and had become disconnected from the reality on the ground. And the New Deal coalition was fracturing, more interested in hating blacks or keeping the “good” suburban lifestyle than in making sure that a rising tide lifted all boats (a prescriptive, not descriptive, statement).

There are those who say liberalism is dying now. That’s true, sort of, in Europe, ex-Britain. The social-democratic European state is being dismantled. The EU is turning, frankly, tyrannical, and the Euro is being used as a tool to extract value from peripheral nations by the core nations. But in the Anglo-American world, liberalism was already dead, with the few great spars like Glass-Steagall, defined benefit pensions, SS, Medicare, welfare, and so on, under constant assault.

Europe was cushioned from what happened to the US by high density and a different political culture. The oil shocks hit them hard, but as they were without significant suburbia, without sprawl, it hit them tolerably. They were able to maintain the social-democratic state. They are now losing it, not because they must, but because their elites want it. Every part of the social-democratic state is something which could be privatized to make money for your lords and masters, or it can be gotten rid of if no money can be made from it and the money once spent on it can be redirected towards elite priorities.

Liberalism died and is dying because liberals aren’t really liberal, and when they are, they can’t do anything about it.

None of this means that modern conservatism (which is far different from the conservatism of my childhood) is a success if one cares about mass well-being. It isn’t. But it is a success in the sense that it has done what its lords and masters wanted —- it has transferred wealth, income, and power to them. It is self-sustaining, in the sense that it transfers power to those who want it to continue. It builds and strengthens its own coalition.

Any political coalition, any ideology behind a political coalition, must do this: It must build and strengthen support. It must have people who know that, if it continues, they will do well, and that if it doesn’t, they won’t. Liberalism failed to make that case to Southerners, who doubled down on cheap factory jobs and racism, as well as to suburbanite GI Generation types, who wanted to keep the value of their homes and knew they couldn’t if oil prices and inflation weren’t controlled. Their perceived interests no longer aligned with liberalism and so they left the coalition.

We can have a new form of liberalism (or whatever we wish to call it) when we understand why the old form failed and can articulate the conditions for our new form’s success. Maybe more on that another time.

If you enjoyed this article, and want me to write more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.