This is the best single book I’ve ever read on morality: About how we should treat each other, especially at the social level. It’s not a good book because Sandel, himself, has much that’s worth saying (though he tries at the end), it is a great book because Sandel is a great teacher of other people’s ideas, able to break them down cleanly, show the logic, and make clear both their problems and their virtues.

Sandel breaks the world’s ethical traditions down into welfare maximization, freedom, and virtue maximization, with a section trailing afterwards dealing with questions of loyalty and particularity. As with all the books I review, I can’t do this full justice, and I urge you to read it yourself, but I’ll sketch out the basics.

Sandel starts with Utilitarianism: This is the principle of the most good for the most people. Utilitarianism is a pared down system: Pleasure is good, pain is bad. We should maximize pleasure, and minimize pain, and nobody’s pain or pleasure is worth more than anyone else’s.

The obvious problem with Utilitarianism is that, in its pure form, it suggests that if a minority needs to suffer so that a majority may know pleasure, that’s acceptable. The most good for the most people even demands it. If I have to kill Fred, even if Fred is innocent, to save two other people’s lives, I do it. If I have to sacrifice an old man’s life to save a young man’s life, I do so. I do so even if they don’t consent.

Utilitarianism shares a problem with the freedom traditions, as well, in that maximization of pleasure doesn’t necessarily discriminate between pleasures. We want to be able to say that taking pleasure from the pain of others is bad: Sandel uses the example of a football player who kept dogs and made them fight himself. The football player took pleasure in this, as a society we certainly allow animals to be mistreated (no, no, don’t pretend), so what, exactly is the problem?

We simply don’t all agree on what is good: We don’t even agree that all pleasure is good. Most people would say sadism is bad; others would say it’s ok if the victim consents; and others would say that self-harm is bad and should be discouraged or forbidden. Even if that includes drinking a lot of pop (definitely self-harm, if not as immediate as suicide).

This leads to Libertarianism, which Sandel uses as his overaching term for the idea that individual freedom is what matters most. So long as what someone is doing harms only them, it is no one else’s business AND society has no business choosing between people. If making ten people better off requires hurting one person, we have no right to do that if that person isn’t actively harming them.

This isn’t an abstract question, it goes to the heart of things like taxation. It asks the question: If a bunch of people are starving, do we have the right to take extra food away from people who aren’t starving–if they don’t consent? It is at the heart of all the libertarians who scream “Taxation is theft!”

There’s a deep vein of truth to liberty, “Mind your own business!” that cannot be denied. The idea that no matter how much someone else thinks they know best, damn it, they should bugger off and leave us alone. Liberty is the wellspring of individual rights, of minority rights, of “just because the majority or the stronger wants it and thinks it is good, doesn’t mean it’s right.”

But, humans do not live alone, they live in societies, and what they do affects each other. In fact, the reason you happen to have extra food may be the precise reason why those starving people do not have enough (in every famine, there has been enough food if there had been no hoarding). That the law benefits the rich far more than it does the poor may well be why the rich tend to stay rich and the poor tend to stay poor. The rules of the game, which let you keep your stuff stuff, may not be fair. If they are not fair, what right do you have to say “Fuck you Jack, this is mine?”

Even more, your health and your happiness effects everyone else. If you get sick, unless society is willing to let you suffer, everyone pays for it. (This is at the heart of Libertarian objections to universal health care: You can do whatever you want, but no one else should be forced to fix your problems.) If you have a disease, you may spread it. If you are unhappy, you will make those around you unhappy. And while society could just let people suffer, not only is their misery often not their fault, it feels wrong to most humans.

Which brings us to Kant, who rested his defense of human rights not in the idea that we own ourselves, and no one has a right to do anything to us, but in the idea that humans are rational beings worthy of being treated with dignity.

Kant doesn’t like the idea that everything is worthy. A libertarian, similar to a utiltarian, will say that what one person likes is their business. Kant doesn’t see it that way. If you are not acting in a way that everyone could act without negative consequences, and if you are not acting in a way that is rational, then you are not acting morally.

Your personal preferences are a mess: They are contingent on your specific body, your specific culture, your specific time. They cannot be universal, and they cannot be rational except in ends-means terms (if you want A, do B to get it). They can only be worthy of respect if they are universal, that is, usable by everyone in all times and places without negative effects.

Furthermore, to act on your contingent wants and desires is to be a slave to them, not to be free. You love America because you were born in America: That’s not rational. You follow a religion because your parents did, that’s not rational. You love sugar because your body craves it, even though it’s bad for you. That’s not rational. It’s also not freedom.

For Kant, to be free and to be just, one must act in a way that if everyone acting in accordance with your morals, the world would work well. If your actions cannot scale to everyone without bad consequences, they are not moral.

This is a hard, hard philosophy to follow, demanding a great deal of the practitioner. Even less helpfully, Kant never drills down to describe what the rules of his morality would be, giving nothing beyond a couple of suggestions like, “Don’t lie.”

Which leads us to John Rawls. Rawls’ famous thought experiment was as follows: Imagine you are creating the rules of a society without knowing your place in it.

This is reason shorn of interest. You don’t know if you’ll be male or female, black or white, born in Africa or America, in a strong body or weak, smart or stupid, and so on.

Rawls believes that not knowing where you’ll be in society, or even what body you’ll have, and with how well you’ll do being determined, in essence, entirely by genetics and position (a.k.a. who your parents are and the genetic roulette of their DNA), most people will choose a society where those who don’t do well are well taken care of, one with some inequality, but not a great deal. Inequality will be justified only as it makes everyone better off: that is, if it is necessary to pay people more or treat them better to have enough doctors, do so, but otherwise, don’t.

Better treatment for Rawls, is only justified if it makes everyone better off. This is similar to the justification for inequality in libertarianism, but not identical. Libertarians believe that “value creators” deserve all of the value they create. Rawls thinks they should only get enough to be willing to do what they do.

Rawls expects that his contract will include rights, as well, because you don’t know if you might wind up as a minority. For sure, women will be treated equally, because hey, that’s 50 percent of the population and your odds of being one are high. So again, we’d include equality, or at least a guarantee of rights, because you don’t want to take a chance on grabbing the shitty end of the stick.

Rawls’ contract thus comes out to “utility maximazation, with inequality allowed only to the extent that it increases overall utility, and with everyone taken care of to a minimum acceptable standard with basic rights for everyone, including minorities.”

Rawls concludes that his contract comes out to be a basically social liberal democratic state of the post-WWII era (or the current Norwegian kind), or perhaps to some sort of benevolent autocracy which can be challenged. Critics find this “convenient,” I leave it up to you to decide if, behind the veil of ignorance, it’s the society you would choose.

Having discussed Rawls, Sandel then turns to the specific issue of affirmative action. (Hey, he’s an academic at Harvard.) To summarize, the issue comes down to, “What is the mission of the university?” If the mission is social (“to create a better society”), which is, in fact, what the charters of many universities say, then affirmative action makes sense. If it is to create better people through education, then exposure to people who aren’t like you is probably valuable and that argument can be made to justify affirmative action. If the mission is, on the other hand, to further educate the brightest, if it is a competition for limited spaces, then affirmative action is not justified. (Again, more subtleties in the book, read it if this gets you hot and bothered).

And semi-finally, we come to virtue ethics, which Sandel identifies with Aristotle.

People should get what they deserve and society should be run to create virtuous people.

This is most visible in competitions and in war: A medal for bravery should go only to those who have shown bravery. The gold medal should go the person who ran the fastest. The job should go to the person who can do it best.

People should get what they deserve, and by making sure that this is so, we encourage people to do what is required to deserve the rewards of virtue.

This isn’t the same as libertarianism’s “kill what you eat” ethos. Virtues include charity and kindness and so on. Virtue ethics came out of the polis: the city state. Citizens were expected to act in the interests of the city as a whole, as well as their own interests. People wanted to live with other good people: kind, just, charitable, brave, and so on. Virtue ethics says that it is not good to take pleasure in bad things. If you like lying, treachery, cowardice, the pain of others, and so on, you’re a bad person, and we don’t want a society made up of bad people.

Thus, a well-run society is one that encourages virtue–not just by rewarding it, but by fostering it through laws and education. Good people make good societies, and contra Kant, there are few rules that cover all circumstances. People will have to make judgments throughout their lives regarding the “right thing to do,” and our best chance that they will make the right choices is if they decide as virtuous people.

This, of course, means that we should choose virtuous people as our leaders. (Note that virtue, in this case, includes qualities we would say make one capable, such as being energetic and brave.) But virtuous leaders, alone, are not enough; the mass of the citizenry must be virtuous as well, or the leaders cannot succeed (and won’t be chosen in the first place).

This line of thinking has echoes in Machiavelli, who believed that Republics could only be created and maintained with a virtuous public, and in America’s founders, who believed that eventually Americans would become so lacking in virtue that only an autocrat could rule them.

(I myself would say that virtuous men and women should work for the maximum good, while encouraging virtue and safeguarding individual liberty.)

Having run through these ethical systems, Sandel now comes to his own ideas, which, to my mind the weakest part of the book. He notes our very human desire for particularity–for putting ourselves, our friends, our communities, and our countries first, and he believes that many of these systems do not deal adequately with these needs. Parents do have a duty to put their children first, yes?

I am reminded of a book I read a long time ago, in which an admiral, on finding out his son was in a city he felt he should bomb, bombed it anyway. “I should be a monster indeed if I were willing to kill the loved ones of others, but not my own.”

I think, perhaps, Sandel would have done well to read more Confucian ethics, which deals with the question of family vs. society in some detail. Almost all of us want particularity, we certainly act on it, but our propensity for particularity, in caring for ourselves first, our families second, our friends third, our countries fourth, and everyone else last (and hey, forget animals), is at the heart of many of our problems.

Judge an ethical system by its fruits, insomuch as it is actually followed. We are very aware of the evils of totalizing ideologies, but particularity, with the indifference and tribal warfare it creates, almost certainly has the award for a higher toll of death and suffering.

And yet, you do have to care for your children first.

But, perhaps, not at any cost.

I strongly recommend this book. It will make you think, hard. And that’s the highest recommendation there is.

If you enjoyed this article, and want me to write more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.

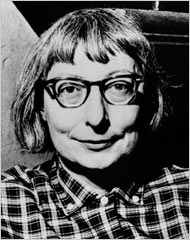

I read this book in the early nineties, along with its companion, Cities and the Wealth of Nations. It struck me then as profoundly important and still does today–perhaps more important than The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the book for which Jacobs is better known and which has become seminal for much of modern urban planning.

I read this book in the early nineties, along with its companion, Cities and the Wealth of Nations. It struck me then as profoundly important and still does today–perhaps more important than The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the book for which Jacobs is better known and which has become seminal for much of modern urban planning.