The Great Depression was cause by a demand problem: there wasn’t enough demand for goods, prices crashed and so did employment.

The policies put in place by the New Deal were almost all intended to increase demand and prices. Farm support, social security and so on. Elites were slaughtered by the great crash of 29 and the Depression. Not all supported the New Deal, in fact many don’t, FDR bragged they hated him. But obviously FDR had elite support.

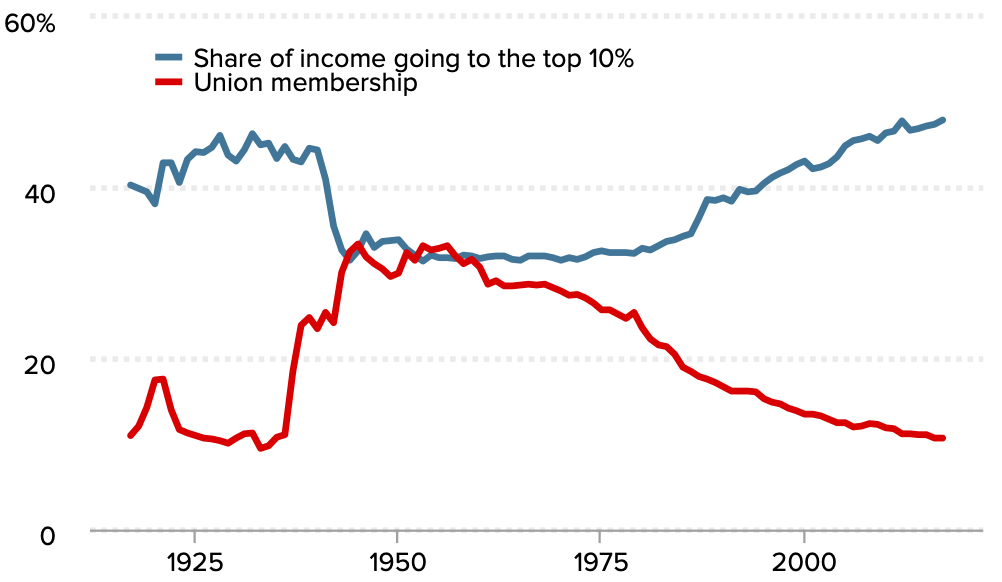

This chart shows what happened:

I think that’s pretty clear. Union membership soars with new Deal, plateaus, then slowly declines. Elites after WWII were not nearly as scared, the economy was good, and Truman’s veto was over-ridden when an anti-union bill which made foreman inelligible for union support passed.

Over time public support for unions also declined. What happens is that those who remembered the depression and the time before it age out: we’re not talking GI, we’re talking Lost and older generations. The GI saw the depression, but they didn’t experience the roaring 20s. They didn’t get what life was like before all the wage, price and demand supports put in place by FDR.

But the mid 70s these people are out of power: not only was there a wave of deaths, but in the 70s there was a movement to replace them in Congress. The incomers wanted process fairness, not outcome fairness and they replaced the old timers. (Matt Stoller has written about this extensively.)

Soon afterwards the neoliberal era dawned, and its intention was to make the rich richer and everyone else poorer: to crush wages, ostensibly to deal with the supply shock by stopping people from consuming goods and services which required petroleum products. Children of the 70s supply shocks, they were terrified of inflation and figured that rich people don’t produce inflation which matters. (This is before the era of private jets.)

In general all successful political action requires some part of the elite to support it. It doesn’t have to be all, it doesn’t even have to be a majority (it wasn’t during the New Deal) but it must exist. Popular support is a power source, but it requires transmission and an engine to turn it into action.

Close to the end of the annual fundraiser, which has been weaker than normal despite increased traffic. Given how much I write about the economy, I understand, but if you can afford it and value my writing, I’d appreciate it if you subscribe or donate.

By Bruce Wilder

Sometimes a comment is better than the post which inspired. This is one of those cases . — Ian

The New Deal created a balanced system of countervailing power on variations of the theory that the political power of citizens working together could oppose and balance the power of the wealthy and business corporations. Labor unions. Public utility regulation. Savings & Loans and credit unions and local banks to oppose the money center giants. Farmers’ cooperatives. A complex system of agricultural supports to limit the power of food processors. Antitrust. Securities and financial markets regulation.

Yes, the rich kept fighting their corner.

When ordinary people had it good by the 1960s, they stopped caring. Or maybe their children never started caring, having never experienced the worst oppressions the wealthy could dole out. Friedman’s message was a simple, deceptive one: the economy ran itself. Government was irrelevant, the problem not a solution. Consumers had sovereignty over business in “the market”. The New Deal as political project ran out of steam as politicians stopped thinking that “fighting for” the common man, the general welfare, the public interest was a genuine vocation or a vote-getter. The rhetoric continued to be used by Democrats to the turn of the century, but the meaning had drained away with emergence of left neoliberalism in Carter’s Administration.

Friedman had an apparently persuasive theory of the case that he made align with people’s desires and illusions.

The institutional base of the liberal classes eroded away. The intellectual basis faded rapidly. FDR’s agricultural policy was one the most successful industrial policies ever enacted. I have never encountered a reputable economist, even a supposed specialist in agriculture, who could even outline its main features. Most take the Chicago line that it was all smoke and mirrors, an illusionist’s trick — that the tremendous shift in resources and growth in productivity was “a natural” emergence that would happen anyway despite gov’t policy. Nixon subverted the whole scheme, helping to make the whole population sick and fat. Nothing to see here. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

The disastrous deregulation of banking and finance was a far more public spectacle than the dismantling of agriculture, but it has never provoked any sustained political movement in favor of even the simplest reforms, let alone a theory of financial reform. Watching “It’s a Wonderful Life” at Thanksgiving is as close as most come to the intellectual outlook of the New Deal.

I have heard it as the theory of 500. Societies of more than 500 or so require institutions of collective government to prevent the worst sort dominating everyone else and the worst usually manage to subvert government to their own ends any way, making the state an agent of oppression. FDR managed to pull together a wildly disparate coalition to create a government that succeeded for a time in constraining the worst impulses of the wealthiest and the business corporations.

It has failed in large part because the many could not remain even minimally organized or informed, free to even a small degree from cheap manipulation of impulse and prejudice.

And From Purple Library Guy:

And this is the fundamental problem with social democracy in general. While they’re in power they can make a nice system, but since it’s predicated on allowing people who want to trash that system to still control most of the wealth, it will inevitably die fairly soon.

I’m just finishing up reading Ed Broadbent’s book “Seeking Social Democracy”, and I found myself impressed by his decency, his erudition, some of his takes on practical politics . . . he was a good man, a very good man. But, he didn’t really grapple with this fundamental issue which in my opinion dooms his project.