A couple years ago I read “The Dawn of Eurasia” by Bruno Macaes. Macaes was a member of Portuguese government, very neoliberal and fairly awful while in office, but his book proved quite insightful in most areas outside of Russia, where what seems to be fear and contempt for Russia distorts his vision. (I thought this when I read it before the Ukraine invasion.)

He’s most worth reading about Europe and the EU, and one example and one passage particularly struck me at the time.

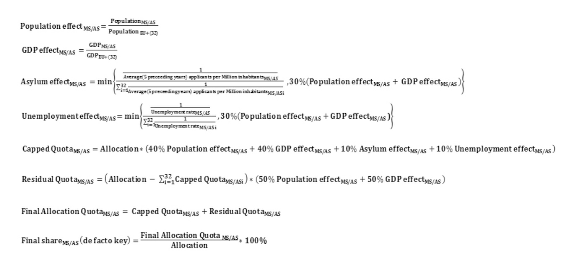

This is the formula for accepting immigrants during the refugee crisis.

Macaes writes:

I was reading the account of the meeting in my office when it suddenly hit me. The European Union is not meant to make political decisions. What it tries to do is develop a system of rules to be applied more or less autonomously to a highly complex political and social reality. Once in place, these rules can be left to operate without human intervention. Of course, the system will need regular and periodic maintenance, much like a robot needs repair, but the point is to create a system of rules that can work on their own. We have entered the end of history in the sense that the repetitive and routine application of a system of rules will have replaced human decision.

Maçães, Bruno. The Dawn of Eurasia (p. 228). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Weber famously called bureaucratization an iron cage: rule by rules and not people, everyone in the same circumstance was supposed to be treated the same, and who the bureaucrat was didn’t matter: once the rules (in modern terms, the algo) had been set up, the human was just a piece of machinery.

It’s for this reason that technocrats love computers and algorithms so much; they make it almost impossible for ordinary humans to override the rules.

Many years ago I moved from Ontario to BC. My Ontario health care coverage was ended. I applied for BC coverage, but then, unexpectedly, I returned to Ontario. I had no coverage. I went to the provincial health office in person, told the person at the desk, they summoned their boss and it was explained to me that there was a six month wait, but they would fix it.

How? The only way was to finangle the system so it thought I had never stopped having Ontario coverage. There was no human discretion, just a flaw in the system which allowed them to do something they really shouldn’t have done. (This is over 30 years ago now, which is why I feel free to mention it.)

If they hadn’t, I’d have had no coverage anywhere in Canada and I was extremely sick and needed health care right away. (Which is probably why they did jiggle the system.)

The idea of bureaucratization was a good one: previous to that offices had been filled by people with a great deal of latitude, which many of them abused to help their friends and family and to enrich themselves. Even when they didn’t abuse the office, they were inconsistent, and no one knew what the rules really were and thus couldn’t plan. As Weber points out repeatedly, you need calculable law and administration to allow modern capitalism. Decisions don’t necessarily have to be good, but they do have to be consistent, or you can’t plan and one unexpected decision can destroy your business.

We moderns will note that the promise of bureaucratization hasn’t really worked out: it’s been subverted. The rules are made and somehow they always favor the rich.

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.

—Anatole France

Now, the law has always favored the rich, but the idea of bureaucracy combined with democracy was that it would do less of that. In some time periods it did, and does, but in most all it did was change the type of rich it favored, moving from aristocrats and clergy, to oligarchs.

The EU, however, firmly believes in bureaucratization, as Macaes notes. It is what is good. The rules exist, they are followed, humans intervene only to set up the rules and occasionally tweak them, but otherwise it’s a big machine algo, and it runs like that. If it hurts or harms someone, so be it, it is fair, because the rules are being followed.

Macaes has a lovely little anecdote about Brexit and immigration which highlights the issues:

I particularly remember a conversation in Manchester with Ed Llewellyn, David Cameron’s chief of staff, where we tested different ways to reduce immigration numbers, some of them quite feasible. This was during the renegotiation process leading up to the referendum. Llewellyn seemed hopeful for a moment, but then shook his head: ‘These are ways to reduce the numbers. What we need are ways to increase the feeling of control.’

Maçães, Bruno. The Dawn of Eurasia (pp. 231-232). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

What the Brits wanted, in other words, was to have humans regularly making decisions, rather than one algo set up by a committee making the decisions, even if the algo was more favorable to them. Basically, can the Prime Minister or the Home Secretary decide how many immigrants come in? No? Then forget it.

It seems to me that the algo-ing of government, the bureaucratization, is a good thing up to a point: people should be treated about the same in the same circumstances. But as a practical matter, bureaucratization, the iron cage, is used to elude responsibility. “The algo did it!” or, “That’s what the law says!”

Every algo was created by people, and while there are sometimes unforseen effects, what the algo does is the responsibility of people. If it is producing injustice, or poverty, or massive inequality those who created it, or those who are letting it run are responsible.

The more you hard-code an algo, and take people out of its implementation, or create systems which force people to become machines unable to make exceptions, the more the dead hand of the past rules the future, and the more that the few people at the top rule everyone else. When middle and low level bureaucrats can’t actually make decisions, injustice inevitably occurs because virtually ever law or algo has blind spots: events and circumstances it did not and cannot deal with.

The evil of three strikes laws and mandatory sentencing, for example, was meant to prevent the evil of judges using their judgment to let people people off if there were mitigating circumstances. Sometimes that discretion was misused, and it would be a big story, but even more often there would be a case of someone’s third crime being stealing a bicycle or a banana.

The ultimate problem is that there’s no getting away from the fact that humans have to make decisions about humans lives. Even if we wound up in a Wall-E world, served by machines, those machines’ initial programing would have been created by humans.

The principles that exceptions need to be made and that humans need to have some control, and that over-bureaucratization removes low and middle level control don’t change the idea that people should be treated equally in the same circumstances. Provincial laws didn’t intend for any Canadian to not be covered by some provincial health care plan; the algo; the rules, had a gap, and a low level bureaucrat could make it work, at least back in the early 90s (today, who knows?)

The same is true at higher levels. There is no escape from human judgment. Attempts to bind everyone with trade deals which are immune to popular sovereignty; with treaties, and to have secret courts and central banks and so on, are all ways to try to avoid responsibility for results.

The problem with our societies is that elites aren’t held responsible for the harm they cause, nor, by and large for any good they do. We have elections without being democratic, because the feedback systems are broken.

All that has happened with bureaucratization, is that the rich still get taken care of, and the poor still get fucked, and it’s done in a way that seems “fair”.

“The algo said” is just a modern version of the “the law says” and it’s just a way to disempower almost everyone while making sure power and money are concentrated at the top.

Any algo or law which doesn’t allow for human discretion to override the algo, with a review mechanism for people who do it often, will do more evil and prove more anti-democratic than even venal spoils systems, which at least don’t pretend that office-holders and other powerful people don’t make decisions and aren’t responsible for their results.