Week-end Wrap – Political Economy – July 27, 2025

by Tony Wikrent

Trump not violating any law

‘He who saves his Country does not violate any Law’

Trump Stuns By Saying ‘I Don’t Know’ When Asked Directly NBC’s Kristen Welker ‘Don’t You Need to Uphold the Constitution?’

Joe DePaolo, May 4th, 2025 [mediaite.com]

A Show of Force

Fintan O’Toole [The New York Review, July 24, 2025 issue]

What Trump was trying to demonstrate in Los Angeles is that he can project his armed power into every American community at any time….

…the primary goal of Trump’s deployment of troops on the streets of Los Angeles is not the violent suppression of dissent. It is the remaking of the army itself. Trump is instructing the troops on how they must think of themselves and of the nature of the country they are pledged to defend….

…putting troops on the streets of Los Angeles is a training exercise for the army, a form of reorientation. Soldiers are being retrained for loyalty to the president rather than the Constitution….

In this light, it actually suits Trump’s purposes if his federalization of the National Guard is understood to be illegal. His deployment of troops in Los Angeles is intended to dissolve boundaries—between domestic disputes and foreign wars, between reality and performance, and above all between a law-bound democracy and arbitrary rule. Getting soldiers used to following illegal orders and to disregarding their “duty to disobey” is a big step toward autocracy.

Trump Promised to Be a ‘Peacemaker’ President. He Launched Nearly as Many Airstrikes in Five Months as Biden Did in Four Years

Alex Woodward, July 17, 2025 [The Independent, via defenddemocracy.press]

Civic republicanism

Governmental Decompensation: What happens when an entire government goes into psychological collapse?

Jim Stewartson, July 22, 2025 [MIndWar]

…Trump’s ego is in a state of panic. His narcissistic supply is dwindling and he’s grasping for anything to bring him love and praise from his cult. This is causing him to decompensate which is the breakdown of psychological defenses under stress, leading to:

- Loss of coherent functioning

- Emotional dysregulation (rage, paranoia, despair)

- Reversion to more primitive coping mechanisms (denial, projection, magical thinking)

But I think we’re seeing something new here, a uniquely 21st century phenomenon. The Project 2025 purge of the government, and the cast of kakistocratic sycophants Trump has installed, along with true ideological psychopaths like Tom Homan and Stephen Miller, have fused Trump’s psychology onto the entire governmental apparatus. In Trump’s first term, he was unsuccessful in fully dismantling the system; there remained a safety zone between his psychological state and the behavior of the federal government. That is deleted now.

To coin a phrase, I think what we’re seeing is governmental decompensation.

The US federal government has lost its coherent functioning. Just this morning, with the explicit purpose of avoiding a vote on revealing the Epstein files, the Speaker of the House Mike Johnson shut down Congress, and went on vacation until September. This is similar behavior to the Supreme Court of the United States throwing America to the wolves and going on vacation until October….

So what are the ramifications of governmental decompensation? What happens to a government if it remains completely fused to a malignant narcissist cult leader’s spiraling psychological state? Well, nothing good.

- Collapse of Trust

The public no longer believes institutions can help them.

- Militarization of the Executive

Police, intelligence, and military become extensions of the leader’s paranoia.

- Normalization of Absurdity

The public is forced to nod along with delusions—or risk punishment.

- Reactive Brutality

Repression increases not out of strength, but out of fear of exposure.

- Fragmentation or Catastrophic Purge

Eventually, one of two things happens:

- A violent purge consolidates a totalitarian regime.

- Or the state collapses under the weight of its own incoherence and infighting.

[TW: Stewartson irritates some people, but he often finds and identifies a psychological indicator that others miss. Similar, I think to how most people fail to understand how power and wealth corrupts individual souls, as explained in the classics of civic republicanism.]

Clowns in a Hall of Mirrors—With Guns — Why the Media Keeps Getting the Trump Regime Catastrophically Wrong

Jim Stewartson, July 26, 2025 [MIndWar]

…Nevertheless, the media, to the extent it still functions at all, has not changed the way it thinks, and talks, about what’s going in America. They still cannot, or will not, face the facts that this is not a group of rational actors, it is a troop of evil clowns in a hall of mirrors—with guns.

We are not watching 4D chess or “Art of the Deal,” the entire US government, and now the nation along with it, are an unstable formation hastily fashioned onto the disintegrating psyche of a malignant narcissist in collapse.

Donald Trump has, through purges, propaganda, and the elevation of loyal incompetents, effectively fused his own psyche—and all its attendant pathologies—to the machinery of the U.S. government. What now governs America is not a coherent system of policy and process, but a state mirroring the ego, paranoia, cruelty, and collapse of a single man.

If you don’t grasp this foundational truth, everything you observe will be filtered through a lens that distorts rather than clarifies. You will see chaos and mistake it for strategy. You will see sadism and call it policy. You will see collapse and label it politics.

And if you report what you see through that faulty lens, you are not just misleading your audience—you are robbing them of the only framework that makes sense of this collapse. At best, you’re depriving them of clarity. At worst, you’re trafficking in disinformation that could get people killed….

Wealth series 7: The real cost of flaunting it

Richard Murphy, July 26 2025 [taxresearch.org.uk]

This video explores how the wealthy flaunt their wealth—not with numbers, but through displays of power, privilege, and consumption. From gold-plated cars to opera picnics and £50 notes burned in front of beggars, conspicuous consumption defines status in our unequal world. But what damage does that do to the rest of us—and to them?….

All of this is designed for one purpose. It is designed to make us envious. The wealthy want us to be envious of them because that gives them the dopamine hit that they crave, which creates the value in their mind as to who they are.

This is the basis of their self-worth. They’re desperate for attention, and without it, they are nothing.

But this is an enormously damaging process. The resources and talent wasted on producing this pointless luxury, which does nothing more than signal that somebody can afford to buy in, are enormous.

Everybody is being driven into a less-than-zero-sum game of status as a consequence of it, and that is always destructive. In other words, we are being told we are not good enough and can never match what they are, and we know that, and therefore divides are created, and that’s why we’re all worse off. And this harms wellbeing.

It harms our wellbeing because we are being told we’re not good enough, and it harms the wellbeing of the wealthiest as well, because actually they become paranoid about the fact that they might not be wealthy enough to keep up with their neighbours, or those whom they meet, or whatever else it might be. The harm is everywhere to mental health….

Wealth series 6: Wealthy, or worried?

Richard Murphy, July 24, 2025 [taxresearch.org.uk]

…the thing that the wealthy are most worried about is losing their wealth. There is nothing that they probably worry about more than falling down the pecking order in society.

The wealthy think they’re top of the pile.

They aren’t sure they’re worth it. In fact, they suffer very badly from impostor syndrome, which is what we suffer if we’re trying to take on a role we aren’t really sure that we should possess, and as a consequence, losing their wealth is their greatest paranoia of all….

So they use their money to protect that privilege, and that’s why they fight governments. And this matters. There is a real cost to their behaviour, not only in the undermining of regulation and everything else that goes on, and the methods that they use to fight fair taxation and all of that, but there’s also a cost to something else, and that is the cost of their hoarding, because remember, they hoard money. That’s how and why they’re wealthy. If they didn’t have hoarded money and value, then of course they couldn’t be considered to be wealthy, but as I’ve explained in other videos, most of saved money is dead money….

How Liberalism Sabotages Itself — Our intentional blindness to bad faith is a loophole fascists use to gain respectability and power.

Brian Beutler, July 25, 2025 [Off Message]

…Several exchanges from this debate have made rounds online—when Hasan gets a boy named Connor Estelle to admit he is a fascist, when another says Hasan should “get the hell out” of the country. But, to me, one of the most revealing moments lacked that kind of viral potential. It was when Hasan asked Estelle: if you hate democracy so much, why are you engaged in public debate, a cornerstone of the democratic process?

“It is the means to support an end,” Estelle responded. “The reason we have free speech now is because we want to be openly talking about our opinions so we can get the state that we want. But it doesn’t mean free speech after we win.”….

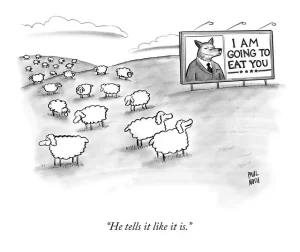

Thanks to Estelle for his honesty. His means-to-an-end-style of bad faith in discourse is endemic on the right—not just among ascendant fascists—and has been for a long time. It’s just that most conservatives will never break character; to the contrast, they take false umbrage if you question their sincerity. But here Estelle lays out the method plainly: Rightists appeal to whomever they can with whatever false commitments they intend to break, knowing that, once delivered to power, they will pull the rug.

In nonexistential instances, this can look like Trump promising to lower costs, knowing that his tariffs will increase them, and (thus) lying about the incidence of tariffs. But in the final showdown, the promise is freedom, and the ulterior motive is tyranny. When Hasan asked Estelle, What happens when your fantasy autocrat kills your family, Estelle didn’t renounce extrajudicial violence. He replied, “Well, I’m not going to be a part of the group that he kills.”

I mention this exchange for two reasons: First, because it’s important for people to know that this is how right-wing operators pursue their ends. That they view liberal freedoms as loopholes to exploit in their pursuit of power. Second, because it reveals a weakness in liberalism-as-practiced.

The liberal commitment to free speech is inviolable. But it does not follow that liberals must extend the presumption of good faith to everyone engaged in free speech. Right-wing operators in particular are groomed and trained to embrace bad-faith argument as a tactic. And yet even in the Trump era, when the bad faith is so thinly veiled, liberals remain reluctant to treat it as disqualifying. Even when their counterparties have established long track records of bad faith….

Trump Is the Most Dangerous Criminal in US History

Thom Hartmann, July 22, 2025 [Common Dreams]

…But Trump’s shady financial dealings didn’t begin or end with these public scandals. For decades, he was closely associated with New York’s organized crime families. Trump Tower itself was built using concrete provided by mob-linked companies.

Roy Cohn, Trump’s mentor and attorney as I detail in The Last American President: A Broken Man, a Corrupt Party, and a World on the Brink, was a notorious fixer and lawyer for mob figures such as Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno and Paul Castellano.

Trump’s casinos also regularly skirted the law, drawing scrutiny from federal investigators for potential money laundering linked to organized crime, and his former casino manager recently revealed to CNN that Trump and Jeffrey Epstein once even showed up together with underage girls in tow (the White House denies the story).

Read More

The current plan is 35% tariffs on everything not covered by the USMCA trade deal.

The current plan is 35% tariffs on everything not covered by the USMCA trade deal.

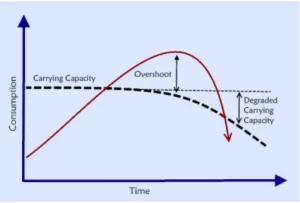

If we were not in overshoot, the environment would not be degrading so severely: massive loss of insects, mammals, acidifying oceans, climate change, rain water that isn’t safe to drink, etc, etc… We’re eating into the carrying capacity of the Earth, producing more than the Earth can sustainably produce, and damaging the Earth in ways which will take ages to fix. Some of them, like loss of biodiversity, are not fixable on any human lifespan.

If we were not in overshoot, the environment would not be degrading so severely: massive loss of insects, mammals, acidifying oceans, climate change, rain water that isn’t safe to drink, etc, etc… We’re eating into the carrying capacity of the Earth, producing more than the Earth can sustainably produce, and damaging the Earth in ways which will take ages to fix. Some of them, like loss of biodiversity, are not fixable on any human lifespan.

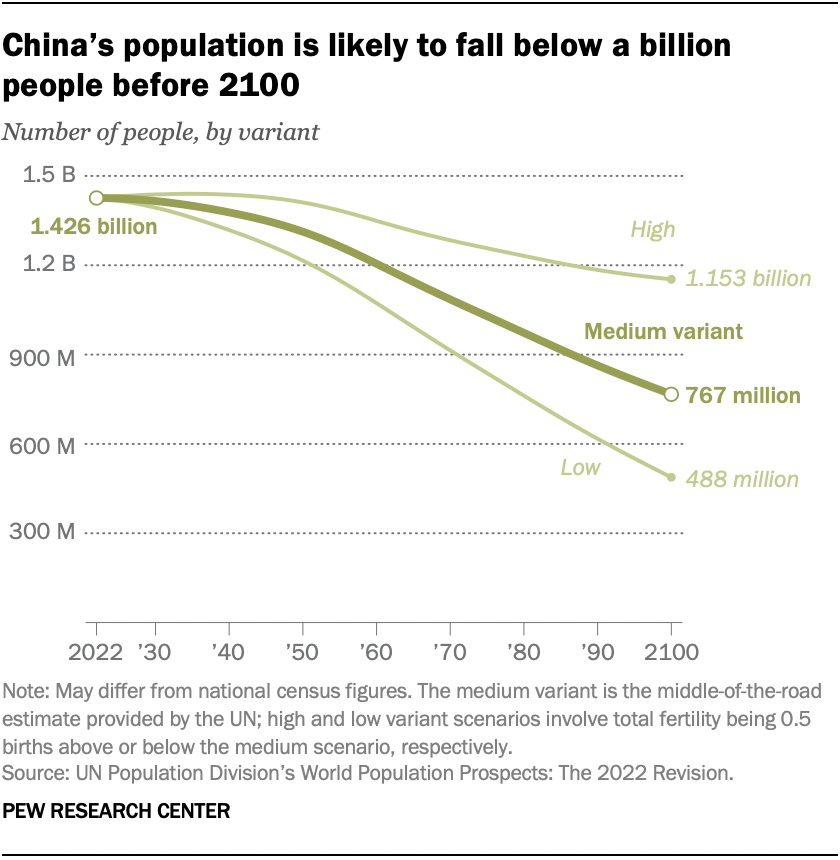

Both China and Japan have been moving hard to “gerontorobotics” (not sure if that’s a word yet.) They know there won’t be enough care workers, so they’re moving to robots which can help people live who are still mostly OK but just old, and they’re also working on robots that can help invalids and semi-invalids, including getting them into and out of bed, helping them bathe and use the washroom and so on.

Both China and Japan have been moving hard to “gerontorobotics” (not sure if that’s a word yet.) They know there won’t be enough care workers, so they’re moving to robots which can help people live who are still mostly OK but just old, and they’re also working on robots that can help invalids and semi-invalids, including getting them into and out of bed, helping them bathe and use the washroom and so on. If you think they wouldn’t do it to you, you’re in lalaland. They’ve proved they are OK with mass murder, and even if you’re white, don’t think it would save you. Look at Trump’s massive health care and food cuts, or Labour’s Starmer taking away aid from disabled people and cutting off heating for old folks, not to mention both being completely callous towards the exploding number of homeless people. In America far more homes are empty than there are homeless people, yet all the vast majority of politicians do is criminalize homelessness more and more.

If you think they wouldn’t do it to you, you’re in lalaland. They’ve proved they are OK with mass murder, and even if you’re white, don’t think it would save you. Look at Trump’s massive health care and food cuts, or Labour’s Starmer taking away aid from disabled people and cutting off heating for old folks, not to mention both being completely callous towards the exploding number of homeless people. In America far more homes are empty than there are homeless people, yet all the vast majority of politicians do is criminalize homelessness more and more. Uber started in 2009. It incurred losses every year until 2023 except for a profit in 2019 which was due to selling subsidiaries in various countries. Numbers before the IPO are difficult to obtain, but it lost 31.5 billion from 2016 to 2022. Let’s assume a loss of equal to funding during the pre-IPO period, so 24.7 billion. This seems reasonable, since Uber never made a profit during the period.

Uber started in 2009. It incurred losses every year until 2023 except for a profit in 2019 which was due to selling subsidiaries in various countries. Numbers before the IPO are difficult to obtain, but it lost 31.5 billion from 2016 to 2022. Let’s assume a loss of equal to funding during the pre-IPO period, so 24.7 billion. This seems reasonable, since Uber never made a profit during the period.