Back in 2013, I wrote an article making the argument that bailouts were responsible for the bad economy.

The reason the economy has not recovered and will not recover for at least a generation is because of the overhang of bad debt, the glorification of financial “profits” (they aren’t), the failure to de-financialize the economy, and the confirmed control of government by the rich.

There is also a section on alternatives to the what we did. “We should do something,” is not the same as, “We must do what we did.”

But, be clear, the economy would be better now if we had not done anything. Yes, the immediate two years after the financial collapse would have been worse, but we’d be better off now than we are.

I think we need to note, first, where we are.

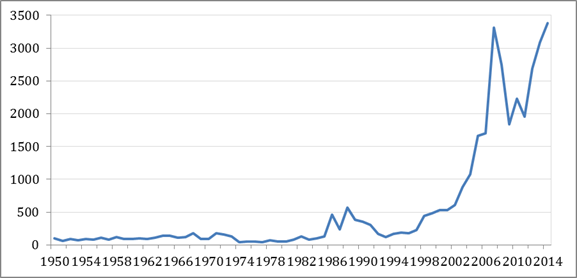

- We are about to go into worldwide recession. In other words, the good part of this business cycle is mostly over. In many countries, it has been over for some time.

- Peak to peak—from the peak of the last recovery to the peak of this recovery, the employment to population ratio has not recovered. It didn’t recover in Bush’s economy either, by the way.

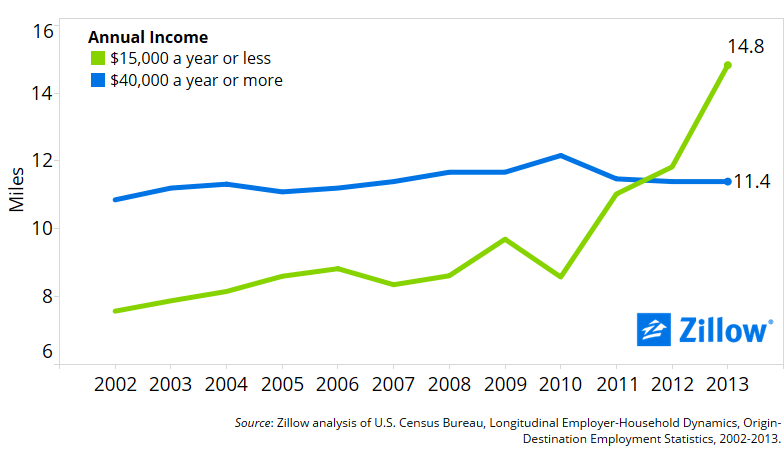

- Median incomes in the US have dropped. This is true in a number of other countries.

- All of the gains of the recovery went to somewhere between the top 3 percent to top 5 percent. And really, that means the top 1 percent, .1 percent, and so on.

- The rich are now richer than they were before the crash.

- China is has hit the mercantile wall. After the financial collapse, they were the engine of global demand. But with so many of their customers in austerity, this could not be maintained.

In other words, the economy never actually recovered. You can argue it did, dishonestly, by looking at stats like unemployment (which don’t consider people who have given up looking for jobs), or GDP, but for most people, this is a shit economy, at best.

It has, however, been a good economy to be rich in.

Now, as I’ve been writing about what Capitalism is this last week, I think it’s worth noting something very fundamental.

The 2000’s economy was sick. It was doing the WRONG THINGS. It was doing them with trillions of dollars. Derivatives such as CDOs, vast expansion of borrowing for stock buybacks, the housing bubble, and so on.

It was doing things which had negative real returns–even measured in money. That these actions had negative, real returns was revealed in the financial collapse when those derivatives were worth ten cents or less on the dollar, and by the fact that central banks and governments had to spend trillions on the bail out.

Measured in human welfare, the mal-investment was worse. When you measure this in “opportunity cost,” meaning what we could have done with those resources instead, which would have increased human welfare, the cost was beyond vast: There are no words.

Capitalism is a system where markets make the primary economic investment decisions through price signals and the availability of money (these are not always identical, which is why I separate them).

More to the point, markets say, “If you are making money, do more of what you are doing.” The assumption is that if you’re making money, other people want what you’re doing, and that what people want is what has the most social utility—the greatest welfare for the buck.

I trust it is obvious to anyone but those brainwashed by the cult of economic utility that, in the 2000’s, the individuals who were making the most money were not creating welfare. They were, instead, reducing human welfare, absolutely and relative to other options.

The other case for capitalism and markets is that they are supposed to be self-correcting. People may make money doing the wrong thing due to market failures, but eventually they will lose that money.

They did.

I repeat, they did. The people making the wrong decisions lost all their money. They lost more than all their money.

We have a shitty economy now because we bailed them out. They then went back to doing all the wrong things, but with a huge debt overhang and more power.

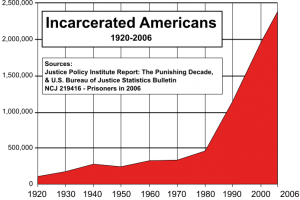

What we needed was new economic decision makers. We needed the people who had all that money to lose their money and thus their political power, making it possible for a different set of people to make money.

Those people would have started off with a lot less money, and a lot less power, and that means there would have been a lot less money in politics, which would have fixed a swathe of problems political, social, and economic.

All that was required for this to happen was to DO NOTHING. Let the banks and brokerages and so on go out of business, and allow the process of law to proceed. The laws on the books at the time made most of what bankers and shadow bankers and various other decision makers doing illegal. Rather than allowing them to pay fines to indemnify themselves against law breaking, actually apply the law. Start with RICO statutes (conspiracy), grab their emails, and prosecute for fraud. (They were, essentially, all engaged in some fraud or another, though I don’t have time to go into that in this piece).

As an additional slice, all their remaining assets would have been seized as proceeds of crime, and they would have had to rely on public defenders.

This is what happens if you just follow the laws and regulations on the books. No special action is needed. None. Except to ensure laws are actually followed, I guess. That it requires special action for rich people to be subject to the law, is, however, part of the point.

So, we have a shitty economy now because we did not get rid of the people making terrible decisions who caused the financial collapse. We have a shitty economy because of the bailouts.

I went into personal decline in 2009 because I recognized that a watershed opportunity had been missed. It was our last chance to get off the train to Hell, really. Oh, we’ll get off that train one day, but we’ll already be in Hell.

The bailouts caused this shitty economy.

Much of what happened was a case of Obama’s decision making, either through action or inaction. TARP passed because he pushed it, for example. Bankers were not properly prosecuted because his DOJ chose not to do so. Many consider the actions of the Fed beyond his purview, but they are wrong.

The full argument is in my pieces “What Can Obama Really Do?” written in 2010, and “Could Obama Have Fixed the Economy?” written in 2014, though I also wrote an absurd number of pieces at Firedoglake on specific policy in real-time. I know for a fact that those articles reached the White House (though I don’t know if Obama ever read them). I know they were included in Dodd’s briefings.

Many other people were writing good proposals at the time as well. People more famous than I. The ideas were available.

So, I once said I don’t hate Clinton. I don’t hate Obama any more, but I did for a long time. He had a historic opportunity to be the next FDR. He deliberately chose not to be, and to instead help and defend the people who caused the financial crisis.

Obama triumphalists who go on about what a great president he is are either misinformed or cockroaches. The true cost of anything is the opportunity cost, and Obama’s opportunity cost is beyond large. Everything he could have done, and did not even try to do.

This is a bad economy, in terms of the numbers that matter to ordinary people. Less have work, and those who do make less money. It is about to get worse. Obama, and yes, Bernanke at the Fed, and Tim Geithner, and various other central bankers and politicians (including, yes, Bush), are responsible for how bad this economy is.

I will add that the most logical, good stimulus, would have been a massive energy project, in which America’s buildings were all retrofitted to be at least energy neutral. It would have directly put to work the people who needed that work, it could not be offshored, with some fairly simple policy, it could have created a solar manufacturing industry in America, and so on.

This means that some of the losses of climate change will also be Obama’s responsibility. Opportunity cost, again.

Enough.

The Obama presidency will go down as a huge failure to historians looking back in even 20 years. The larger point is this: Capitalism does have some virtues, and one of them is wiping out people who are doing the wrong thing. That doesn’t mean that “all bailouts” were a bad idea, but bailouts of the people who caused the crisis (bankers, shadow bankers) were. The primary bailouts caused the lousy economy.

There will be another crisis. Learn the lesson of the last one. If we don’t, well, crises will continue until we do.

If you enjoyed this article, and want me to write more, please DONATE or SUBSCRIBE.